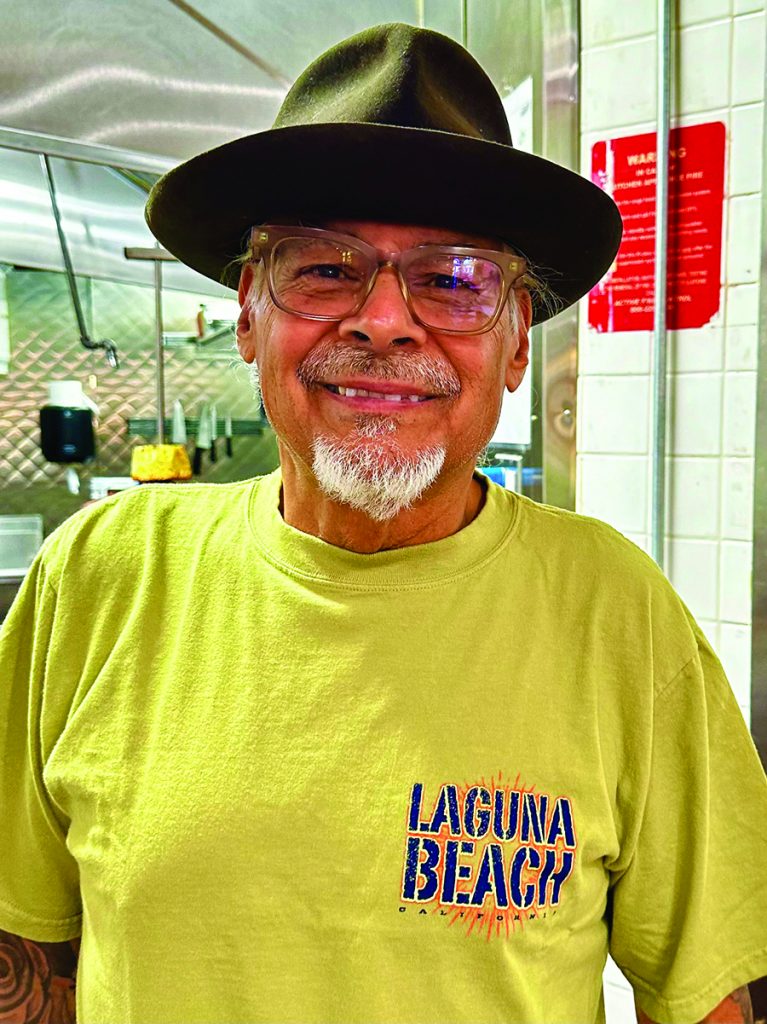

Bhavna Kolakaluri grew up in a small city in South India, in a home where food wasn’t just food—it was ritual, memory, and love. After moving to the U.S., she found that the grocery store spices were flat and flavorless—nothing like the vibrant, aromatic ingredients she had grown up with. Thus began her journey of sourcing fresh spices directly from small family farms in India.

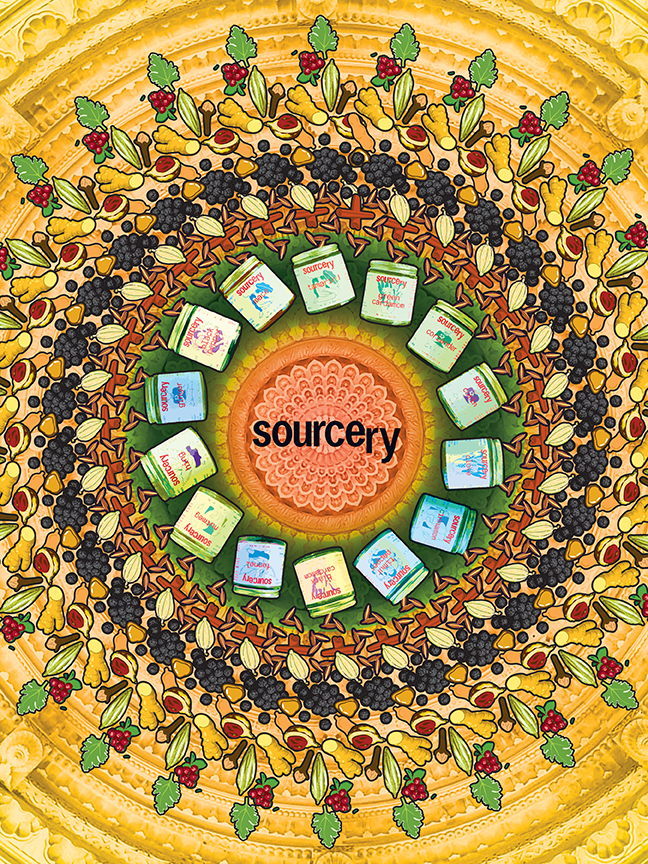

She founded Sourcery in 2023 with the goal of bringing freshness, fairness, and flavor back to the kitchen. Since then, her farm fresh spices have appeared in various farmers markets, CSAs, cafes like IXV coffee in Boerum Hill, and markets across Brooklyn, including Greene Grape Provisions in Fort Greene.

I recently attended an AAPI Heritage Month dinner and had the opportunity to meet Bhavna, learn about her inspiring story, and taste the vibrant flavors of Sourcery for myself.

Angela: Hi Bhavna. Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and how you started Sourcery?

Bhavna: So I grew up in India and moved to New York to go to grad school. Then I worked in food startups like Fresh Direct, Daily Harvest, and Blue Apron where I got to peek behind the scenes of how immigrant food makes its way into the grocery store shelves and onto people’s plates.

I noticed that the richer stories are all stripped away, probably because the people sourcing the foods have not lived in these cultures. At the same time, the Indian food scene in New York was bursting—Semma had opened, Masalawala had opened—and I thought, “Maybe there’s an opportunity for me to do something here.”

My parents live in the southeast of India, in a state called Andhra Pradesh, and I go visit them every year. Sourcery was borne from my desire to deepen my own relationship with my country while sharing my culture with the world.

That’s interesting that you worked at so many food startups. Was food something you’ve always been interested in?

Yeah. My family is really into food so I have all these memories that tie back to food. I grew up in a family where my mom and my dad were both actively making three meals a day, and they spent a lot of time preparing dishes. For instance, to make the batter for dosa, they had to take rice to be ground at the local mill first. But they both really enjoyed the process of cooking.

In the summer during mango season, my grandmother would start the pickling process, so my aunts and my mom, we would all buy mangoes from the markets and cut them up, and the house would smell really wonderful. I loved those moments where all the members of the family would come together and the food made the house smell so good.

I visited a market in my hometown of Qingdao recently, and everything was seasonal and what you saw was what you got. Meanwhile in the U.S., we expect to have everything at all times, even if they’re not in season, and that sometimes translates into cultural meals that are diluted or don’t taste like they’re supposed to.

For sure. Some ingredients you only get for an extremely short period of time, and you really intensely enjoy it at that time, and then wait for another year. And your experience of it is so much richer because of how ephemeral it is.

So one of the things that I wanted to do with the spices I offer is to treat them more like food.

In the U.S. spices are so commoditized that by the time they reach the grocery stores, they’ve been sitting around in warehouses for ages and you don’t know how old the spices are. When people smell my spices at farmers markets, even something as simple as black pepper, they’re like, “Whoa, it smells raisiny!” It really opens their mind to the idea that fresh spices actually taste really good and have real complexity.

That adds to the complexity of the dishes they’re used in, right? And deepens our understanding of their respective cuisines.

Totally.

And there are so many regional foods too that people don’t know about. Like sure, tandoori chicken is popular, but there’s also sambar, which is this lentil blend that you dip dosa in. I remember my mom making it every Saturday or Sunday, and it just smells really nice, because it’s tangy from tamarind and sweet from jaggery.

One of the things I want to do is make more regional flavors like sambar accessible through spice blends.

What sets Sourcery apart? How are your spices so flavorful?

So in order for spices to be really flavorful, there are a few things that need to happen.

One is the seed variety. We opt for heirloom varieties, which are basically what naturally grew and evolved in a specific place.

They usually don’t look as pretty—for example, the heirloom variety of green cardamom is really small, whereas the variety that has been bred for consumption and high yield is really large and green. But in terms of complexity of flavor, heirloom varieties are much better. So I try to source heirloom varieties as much as possible.

I also source from small farms, because people who’ve had land in their family for generations tend to take better care of their land. They intercrop it. They’re not just growing for yield. So I’m focused on finding these farmers who are trying to do things sustainably.

It’s so interesting how these ancient cultures—Mexican, Indian, Native American—all practiced intercropping. They knew about this chemical-free way for different produce to grow synergistically while also preserving the quality of the soil. That ancient wisdom seems lost in modern U.S. agriculture.

I mean, as soon as you treat land to maximize yield and production, then you’re treating it as something that is expendable to some end. And that leads to really disastrous consequences.

Native agriculture or regenerative agriculture is just how agriculture was done a long time ago before industrialization kind of messed it up.

It sounds like sustainability and ethics play a huge role at Sourcery.

For sure. I also aim to pay farmers more than what they would get if they sold in their own local markets or sold to traders or anybody else here. That’s a big value as well.

How do you find these farmers?

It wasn’t easy. At first I thought, “Oh, I’m just going to find them on the internet.” But no, farmers are not on there.

I knew that Andhra Pradesh was the biggest producer of turmeric in India, and there is a market in the town my mother is from where turmeric is traded. So we went to this town and we talked to a bunch of farmers there and asked them to take us to their farms. That’s how we started building these relationships.

Then I discovered that a lot of farmers who grow things organically form networks. They share information amongst each other because organic farming is actually really hard. It’s like a race against nature: you do something, nature does something back. It’s like a chess game and so they have these networks to exchange information.

Once I found a really good organic farmer, he introduced me to other farmers.

Reaching that network is so valuable. You had to know the language, have family in the area, understand the culture… I feel like that’s something that only someone in your position could have done.

Right. Another example of a spice that I wanted to source for a really long time is tamarind. It grows wild in the region that I come from, but it’s in these forests that are really, really dense. There are some tribal groups that live there whose livelihood is foraging wild tamarind, and they bring it to these local tribal markets where traders then buy them for resale.

For a long time, I really wanted to buy tamarind from them. One day my dad and I embarked on this six-hour journey into this town called Chintapalli, in order to track down these foragers and try to buy directly from them.

If didn’t quit my job to do this, I would not have been able to have this experience.

Can you talk about the experience of quitting your job to build this small business?

Yeah. I worked as a product manager and primarily built supply chain systems. So I saw from a distance how businesses are run, but I never thought I would start my own company. I didn’t know a big part of how businesses are run, but I thought, “Okay, I’ve figured out a lot of projects. Like, I can figure this out.”

Two years ago, I received my green card and had the ability to quit my job. So I decided to give myself six months to see how far I could get.

I started sourcing two spices: jaggery and turmeric. Along the way I learned how to do all of stuff like, you know, start an LLC, like, make a website. But I didn’t know anything about marketing. I find it hard to promote myself on social media. The path that made the most sense to me is selling in farmer’s markets, where I’m interfacing with people one-on-one and I’m able to tell them my story in a more concrete way.

I get the sense that Sourcery is very grassroots and it’s very rooted in the local community.

Oh, yeah. When I first started, I set up a table on Willoughby Street with a friend who makes chili crisps. That’s how I made a lot of friends who are other founders in the neighborhood. And from there, I progressed to other markets in the city. A bunch of people introduced me to their friends who owned stores — Sujuk on DeKalb Avenue is one of the stores I was referred to. So it kind of grew very organically.

How has the growth been beyond the first six months?

It’s not been linear. I got the thing off the ground within six months, but I also wasted a lot of time agonizing on all these minor details like which colors and fonts to use. I look back, and I’m like, “What did I do in those first six months? I feel like I just sat at home looking at my website and wondering why nobody was buying anything.”

I also had to develop thicker skin and learn to pitch my product to grocery stores, which I was a bit too scared to do at first.

I just came out of it a little bit stronger with thicker skin, um, and, like, went and started, like, pitching my product to, like, grocery stores, like, to Green Grape, um, and, like, doing these things, which I was, like, a bit too scared to do in the first six months.

When you see other businesses on social media, you don’t know what journey they’ve been through. You see someone who’s very successful now, but we don’t know what they’ve gone through or how long it has taken them. In my experience, it always feels like one positive thing happens and then nothing happens for a while.

I feel like things are starting to click a little bit more, but it’s a very up-and-down ride. You might reach a goal that you’ve set and then you realize, “Oh, this is not it.”

What does the near future of Sourcery look like?

So I started with two spices, jaggery and turmeric, two years ago. Now I have 17 spices. And I’m doing Fancy Foods later this month!

It’ll be my first trade show. I’m excited to see if my product has a shot at a big grocery store and to talk to a big grocery store buyer and see what they do and don’t care about.

I’m also launching spice blends, which I’m really excited about. I noticed that a lot of people actually don’t know how to use spices and I think spice blends actually make it easier for people to start cooking

Do you have a long-term dream for the company?

Oh, good question. I think what excites me most is really the sourcing part of my job. I want to turn that into value for the customer, by sourcing this diverse range of spices from South Asia that people cannot normally access in grocery stores, and like bring really high quality versions of them. I really want to go deep because there are so many spices in South Asia that people don’t know about.

Totally. And I feel like there are so many stories to be told when you do.

It’s a treasure trove. And it’s also a personal journey of exploring Indian cuisine. As I go deeper, I learn more and I find that enriching. Half the reason why I do what I’m doing with Sourcery is just pursuing my own interests.

It sounds like your relationship to Indian cuisine and ingredients changed after leaving India.

Growing up in India, I just consumed what my parents made. I was curious about other regional cuisines, but I didn’t have much access unless we traveled, because I grew up in a small city (of 3 million people obviously). And it’s funny, I had access to a greater diversity of regional Indian cuisines after I came to America.

But also as I got older, I started digging deeper into my roots, beyond what the history books teach. I think that is one of the reasons that prompted me to start Sourcery — it gives me an avenue to spend more time doing this.

Do you have a fondest food memory or a dish that is just so nostalgic for you?

I have very strong memories of food scents.

Like when my mom would make ghee at home. She starts by making yogurt at home and skimming the cream of the yogurt. Over time it accumulates in the freezer until one fine day they’ve collected enough and it’s time to make the ghee.

And it’s melting that hardened milk cream in a pot creates ghee. It makes your home smell so heavenly, and when you make it, there are these brown bits of ghee stuck to the bottom of the pot. My mom used to skim it off and put some sugar on it and give me a taste, and that was always my favorite.