“Ma,” I’m screaming into the phone with the wind still blowing, Brooklyn never wants to loosen its grip on winter. But the wind wants to go. After all, there’s a bunny here! A sure sign of spring.

“What’s wrong?” My mother is on the other side of the country, chomping a bagel out on her balcony. She’s in curlers and a nightgown. I know this because even though I’m in Park Slope and she’s in Palo Alto where it’s three hours earlier, my mother has eaten a bagel in her nightgown and curlers every morning for the past forty-three years.

“Ma, you’re not gonna believe this! I’m chasing a bunny through Prospect Park!”

“You’re chasing a what?” I can hear the crumbs spray off my mother’s lips as she reaches for her mug of milky coffee.

“A bunny, ma, a bunny.”

“What the hell are you talking about? There are no bunnies in Brooklyn.”

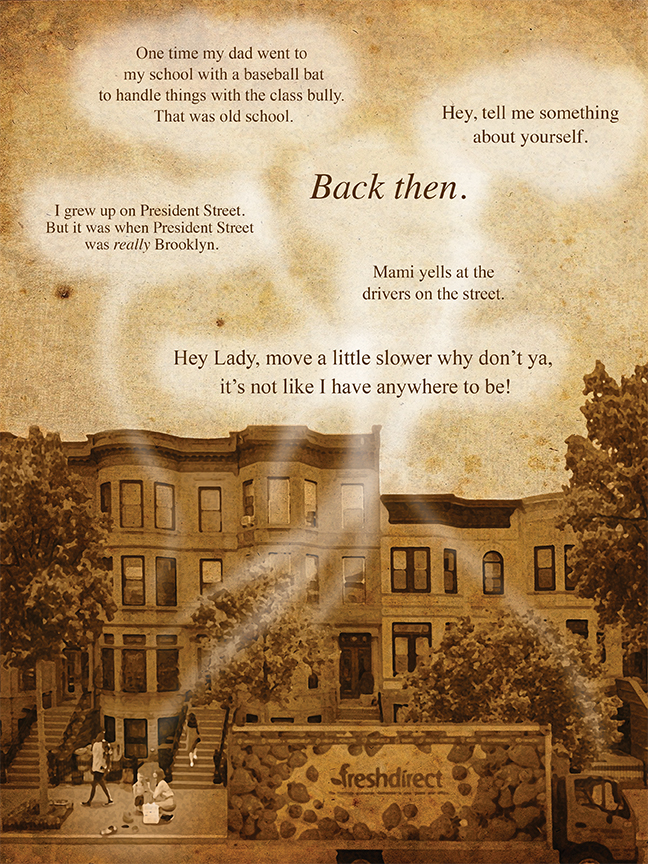

I don’t know why my mother isn’t sitting on the boardwalk in Brighton Beach right now. She’s not the California type. She’s the Mumu on the boardwalk judging people as they walk by type. I mean, she’s yelling, YELLING AT ME, about this bunny. Arguing, really. And you can tell my family is from Brooklyn because I’m arguing right back.

“Ma, how the hell do you know that there are no bunnies in Brooklyn? Are you here right now? Also, did you know that Coney Island was full of bunnies before it became Coney Island? It was called Rabbit Island before it was called Coney Island!”

My mother takes a deep sip of coffee before she says, “Are you in Coney Island right now or Prospect Park?”

“Prospect Park, by Ninth Street,” the bunny crosses the bike path, but I follow.

“Well, you should be at freaking Bellevue in Manhattan because you’re crazy. That’s not a bunny.”

The argument with my mother has not slowed me down. In fact, the angrier she makes me – insisting that this is not a bunny when she is in California, and I am following a bunny – gives me speed. I stay on the phone to argue and simultaneously chase the bunny. I’m not sure what I’ll do if I reach the bunny. It’s not like I’ll pick it up. I think I’m wondering that if I follow it into its home there is a possibility there will be more bunnies. Then I can snap a picture, post it on Instagram and caption it “First signs of Spring in Brooklyn!” Maybe the photo will go viral. Maybe I’ll be on the news. Maybe I’ll make a YouTube channel called “Brooklyn Bunnies” where I discover a new part of this bunny world every day. Then I’ll have tons of followers and be able to pay my bills, and I won’t have to worry so much about the cost of food, if I should sell my soul for a celery juice, or if I can find a brand-new pair of sneakers at a discounted price for my smallest child who’s growing at the speed of light. All of this goes through my head as I yell at my mother who’s eating a bagel on her balcony, and I chase this little animal into the forest.

“Ma, when I finally snap a picture of this thing, you’re going to be in shock. I mean, real shock. Ugh, hang on, I have to climb this fence.”

“Have you seen the news? Terrible, just terrible.” My mother has always had a real knack for changing the subject right at the point when I might win the argument. I put the phone on speaker and hook it into one of my bra straps under my sweater as I climb a fence by the far end of the lawn.

“I haven’t seen or heard the news and I’d like to keep it that way,” I scream this into my chest as I jump down into what looks like an ivy forest just off the path. “I’m done watching the news, it’s making me really crazy and anxious.”

“Well dear, yes, you’re chasing an imaginary bunny into the woods. Aren’t you supposed to be working today?”

I snatch the phone from my bra strap, scratching my neck as I violently pull it out of my sweater. “Ma,” I grit my teeth, “the bunny is NOT imaginary. It’s right here, I just can’t get a picture of it because it keeps moving, oh but when I do…” Before I can finish my sentence, the bunny stops. “Ma, shhhh, hold on, it stopped.” As it freezes, I edge closer. It ruffles the ivy and turns to face me.

“Well, what is it?” My mother has a piece of bagel in her cheek that she hasn’t chewed yet. I can hear it there collecting saliva. She, too, is quiet and unmoving on the phone waiting to see who’s right. Who won the argument this time?

“Oh, wow, well, ok, eeewwww,” I am turning around as fast as I can, running in the other direction, hands shaking, shoving my phone back into my bra, leaping over the fence, taking the phone out again, and bounding across the big lawn at ninth street.

“What, what? What was it?” My mother shouts through the phone.

“I’m not telling you,” I’m still running.

“Now you have to tell me. I told you it wasn’t a G-ddamn bunny! What are you, nuts? What was it a squirrel? A bird? Chipmunk?”

“No, Ma, no.” I really don’t want to tell my mother what I have been maniacally chasing for the past fifteen minutes, but I know that in a real Brooklyn argument, you can’t hide the facts.

“Come on, out with it! What have you been chasing?”

“A rat, ma, a freaking, disgusting, dirty rat, ok?!?” I wait for the cackle of laughter to come, and when it does, I laugh a little too.

“Do me a favor,” my mother is howling now, “if you’re off from work today go get your freaking eyes checked so that you stop seeing Easter Bunnies running around Park Slope.”

“Yeah, ok, Ma.”

“Now have a great day, dear. I love you! I’ve got to finish reading the Times before my ZOOM dance class.”

“Alright, Ma.”

“I can’t believe you just chased a rat through the park. I can’t wait to tell my friends at lunch today!” My mother is still giggling when she hangs up.

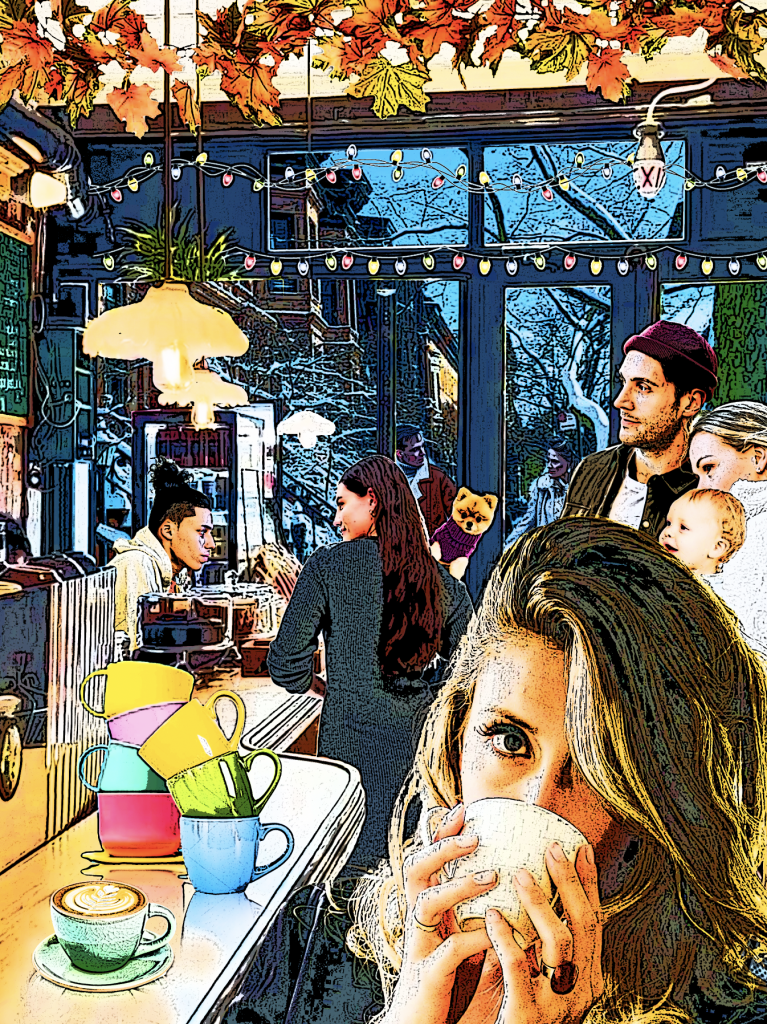

If I really examine this experience, it’s that my heart has been chasing spring before spring has been ready to bloom. The winter was hard this year, and I can’t wait for the daffodils to begin making their entrances around the neighborhood. When will the front stoops of brownstones start showing their pink and blue perennials, their yellow tulips, their purple and white hyacinths? And because I can’t wait for the first bursts of color, those initial signs of hope and life, and the natural progression of things, I force it. Spring in Brooklyn, spring in Park Slope, cannot be forced. Instead, it must unfold, and we must allow it to. The cafes and restaurants up and down Fifth Avenue must set up their outdoor dining when the weather tells them it’s time. Little children exchange their heavy coats for sweatshirts and lighter activewear as the robins begin to appear. The green markets replaces apples and squash for strawberries, rhubarb, and asparagus. Then, and only then, is it spring. Anything else would be like screaming on the phone with your mother while chasing a rat through Prospect Park because you thought it was a bunny. And that would be crazy, right? I mean, who does that?