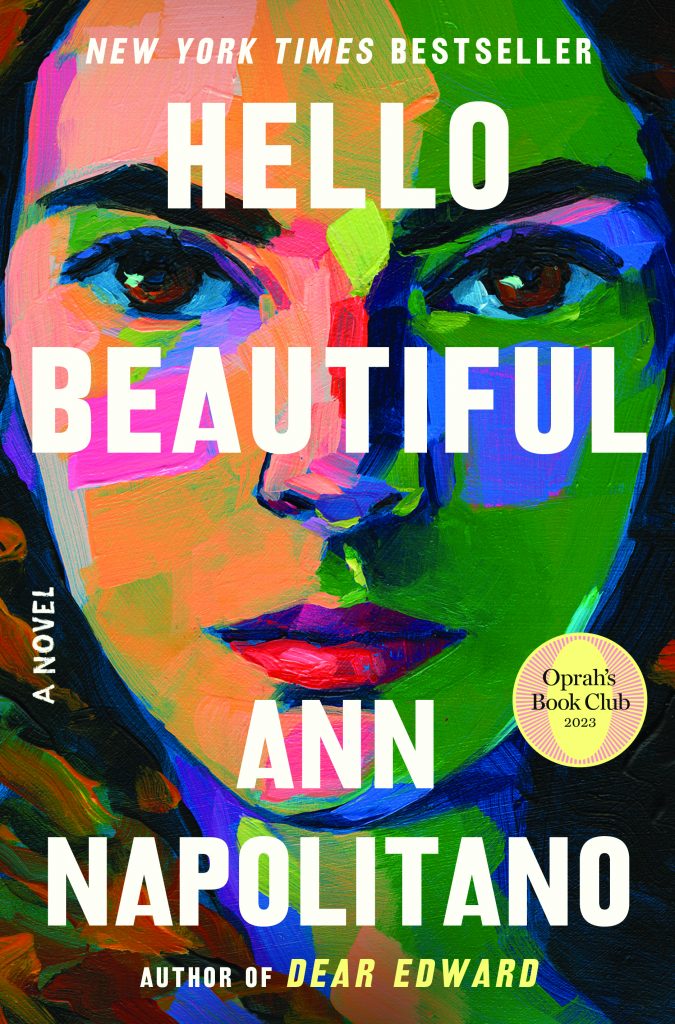

The first chapter of Ann Napolitano’s new novel, Hello Beautiful draws the reader in with a harrowing synopsis of William Waters’ early life in a suburb of Boston. William, a lonely little boy with a basketball, finds comfort in the repetitive sounds of the ball hitting the pavement. His world is narrow; his parents have raised him to be helpless and have deprived him of affection. His mother smokes cigarettes and drinks liquor, while his father, a miserable accountant, works long hours in the city. William’s parents forbid the discussion of his older sister, although they keep a framed picture of her on an end table in the living room. The basketball court serves as a refuge for William. In college, William meets Julia Padavano in a lecture class at Northwestern University. With Julia comes warmth, passion, security, stability, and the saga of living with her three younger sisters and two peculiar parents— under a small roof in a culturally-rich neighborhood in Chicago’s Lower West Side. The four sisters are inseparable. They finish each other’s sentences; they honor one another’s aspirations and eccentricities; and, without hesitation or judgment, they welcome William into their closely-knit kin, despite his uniquely dark past. The Padavano sisters envision themselves as the March sisters from Little Women, foreshadowing the ultimate tragedy that tests their loyalty to one another.

Hello Beautiful poignantly catalogs the devotion of family and the consequences of loss, power, and mistrust. It is a story that sat inside of Napolitano for years, waiting to be told. In a phone call, Napolitano and I discussed the research and real-life events that inspired Hello Beautiful, and why she feels personally connected to the novel. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Hello Beautiful is your fourth published novel, a New York Times bestseller, and Oprah Winfrey’s 100th book club selection. Congratulations! You began writing the novel in April 2020, shortly after the pandemic lockdowns began. Can you tell me more about your experiences in lockdown and the other events that inspired Hello Beautiful?

Yes, I wrote Hello Beautiful in two years. My other novels took between seven and eight years. I began writing during the beginning of the pandemic when everyone in New York City was in lockdown. My dad died that month and because of the pandemic, we were not able to see him while he was dying—and we couldn’t gather after he died. This happened to many families, especially in New York. It was not an uncommon experience but it was very singular to that period. When I started writing, everything happening in the world was so weird. I was isolated and I was grieving my dad. Creating this fictional world had an urgency that, usually when I write, doesn’t exist. This is attributable to what I felt during that time. I needed the world I was creating. I wrote more quickly than I ever have in my life.

The “urgency” you felt to write the novel is interesting. A lot of creatives had breakthroughs in 2020. I have friends who were highly creative and productive in their work, and others—including myself— who shut down. Their creative process was completely hindered by the pandemic lockdowns and economic fallout.

That was my experience too. The writers I know either wrote obsessively or they found that there was no way they could write at all. One reason isn’t better than the other. I think people did what they needed during that period. I’m glad I was able to write because building a new world was helpful when the real world was in shambles. I found it to be reformative and healing. It was nice to have an escape.

I can appreciate that— the visceral act of thinking and writing to otherwise escape the unsettling reality we were all living in. Would you say that writing the novel also served as a catharsis? Parts of the narrative arrived from a place of grief.

Early in the book, the father of the Padavano sisters dies. I didn’t know he was going to die when I was writing. That surprised me but I also was able to go through a wake and a funeral for that father when I couldn’t for my father. Writing the story provided me with experiences that I craved and couldn’t have in real life. I didn’t plan that— it was completely dictated by the story. The story was filling empty holes inside of me in a way that I had never experienced through writing. There was a personal intensity to the emotions in the book, even if what happened at various points in the story were not actually from my life. This feels like my most personal book because my grief and the things I was struggling with pan out in the storyline.

Other elements in the novel are personal to you for various reasons. In an interview with Oprah on The Oprah Winfrey Show, you said the narrative was “sitting inside” of you.

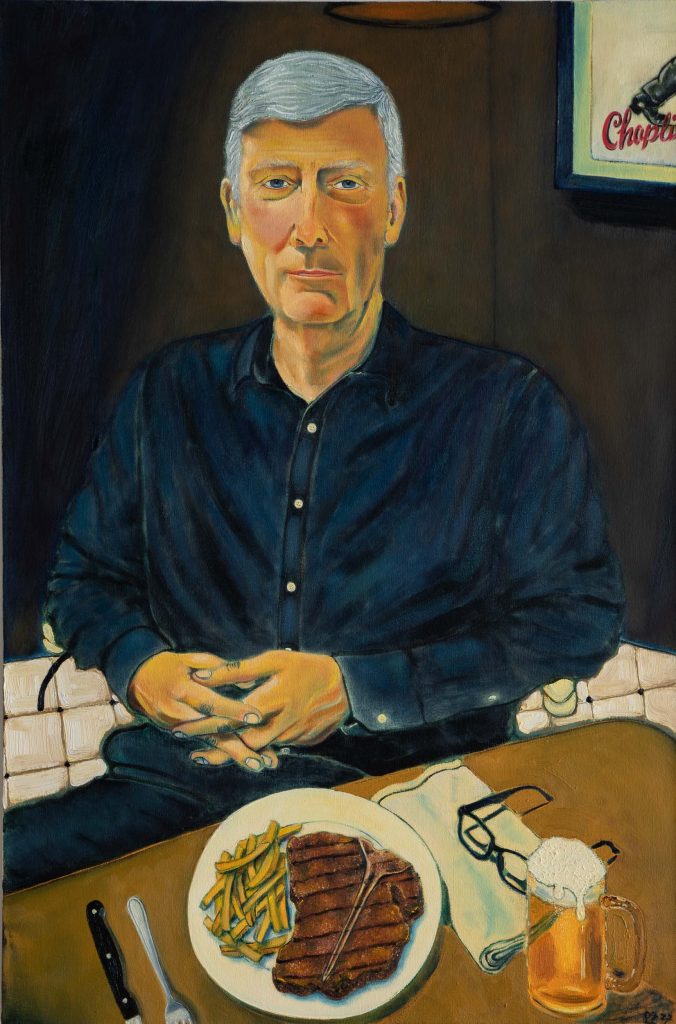

Yes. I am woven through this book. Personal stories from my family are what started the book. My uncle, who lived in Chicago, would mail me postcards as a little girl. He always addressed them as, “Hello Beautiful” and that’s what the father in the book— Charlie Padavano— says to his girls. The book is set in Pilsen, the neighborhood in Chicago where my uncle lived. I have a hazy sense of the neighborhood, in this faraway city, that seems magical and fictional. It makes sense that I would build this world in that neighborhood. And Leah, my best friend growing up, had five aunts who went in and out of the house all the time. I was fascinated by them. I used to watch them like they were on television. How they would finish each other’s sentences and how they understood each other completely. They were more whole when they were together than when they were apart. Leah’s mother and her aunts inspired my Padavano sisters.

Both you and your character, Sylvie Padavano imagined a sad boy dribbling a basketball. You write: “Sylvie tried to imagine what it would have been like to grow up in home with no affection or laughter and envisioned a cold, echoing space. She saw a little boy dribbling a basketball in order to make a comforting, repetitive sound.” (p. 193)

Can you further discuss the vision of the young, sad basketball player and your vested interest in the sport?

I always tell my students that they should pay attention to their obsessions because often, the weird things that pull one’s attention will materialize. A few years before I wrote Hello Beautiful, I became obsessed with the history of basketball. I was reading about the history of social justice and was interested to learn that the history of basketball runs parallel. There are amazing figures like Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar who had great strides in civil rights. I was fascinated with the history of basketball— so I knew I was going to put that into the book. I can’t articulate why that was so meaningful to me but it was, and it was meaningful to William too, the main character. My obsession with basketball showed up through his lens.

William Waters, the four Padavano sisters, and many others had significant roles in the story. How did you write the characters?

For the last two novels, Dear Edward and Hello Beautiful, I did this thing where I would finish the book and then for nine months to a year, I would not let myself write “pretty” sentences— which is what I like to do the most. For example, I like to write a scene and then have a character walk in and say something I didn’t expect. It’s like being a reader because it’s an act of discovery. When I’m doing that, I can’t think analytically. I can’t figure out what makes sense for the story because it’s all intuitive. So, for the first nine months to a year, I don’t let myself write “pretty” sentences. I research, think, take notes, and try to figure out what kind of story I want to tell. I try to figure out who is in the story and what is the most interesting aspect about each interaction and scene. There is a lot that I figure out during this stage, and the characters are part of that. When I actually begin writing, a lot of the notes do not get used. The notes are extensive but will turn out to be wrong. Fortunately, the time I spend mapping out the characters and thinking about them does make them three-dimensional and real. This exercise gives me a starting place that feels solid. I feel like I know them from the first page, and then their stories evolve from there. They surprise me, and again, the intuitive part takes over.

Researching the historical scope of basketball, coupled with the image of a sad basketball player, became an obsession. Do you find that you are constantly thinking about the characters until the book is in its final stages or published?

Yes. For example, with basketball, I knew that I was fascinated with the history of the sport. Before I began writing the book, I thought that the character of William might become an NBA physio— which is a person who assists athletes with their bodies. I interviewed an NBA physio in LA while I was there on tour. I try to explore every possible idea that I have and everything that excites me during that period of writing the storyline and developing the characters. This practice is helpful so that when I start writing, I know who they are. They do end up in situations that are unexpected and the deeper work of writing is trying to figure out the right response of the character.

Do you ever find that you need separation from the characters or do you continue to work through creative challenges?

My previous books took many years. When I was writing Dear Edward, I would walk into the world of Edward and build the story inside of it, and then leave it at the end of the day. I would continue to think about it— but I would leave it. That was enjoyable. With Hello Beautiful, I was feverish. The story was living inside of me and the only way for me to get any peace was to figure it out. There was tension and urgency. The only way to not make myself sick over it was to write and get the characters’ stories right. I had no break from it. I was always thinking about it. It felt very important.

In an Instagram post, you wrote that the reason you write is to “make sense of yourself and the world”. I think a lot of artists, regardless of medium, would agree. They are writing or painting or making music about the things they are experiencing. Creating can be enjoyable, albeit compulsive, but it’s also work. The concept of “work” sometimes gets lost.

I think that’s true because if you’re not an artist, the concept of “art” sounds more meaningful than what a person may think of as “work.” Often, people look with a certain amount of longing at the idea of having work that is so meaningful and rewarding. Art is romanticized, but of course, it is also challenging and difficult. It requires all of me when I’m doing it. It requires all of my experience; all of my curiosity; all of my interests and attention; all of my striving for excellence— everything. There is no way to half-ass it and have it be any good at all. I write because it is the most fulfilling, self-engaging activity I can conceive of doing.

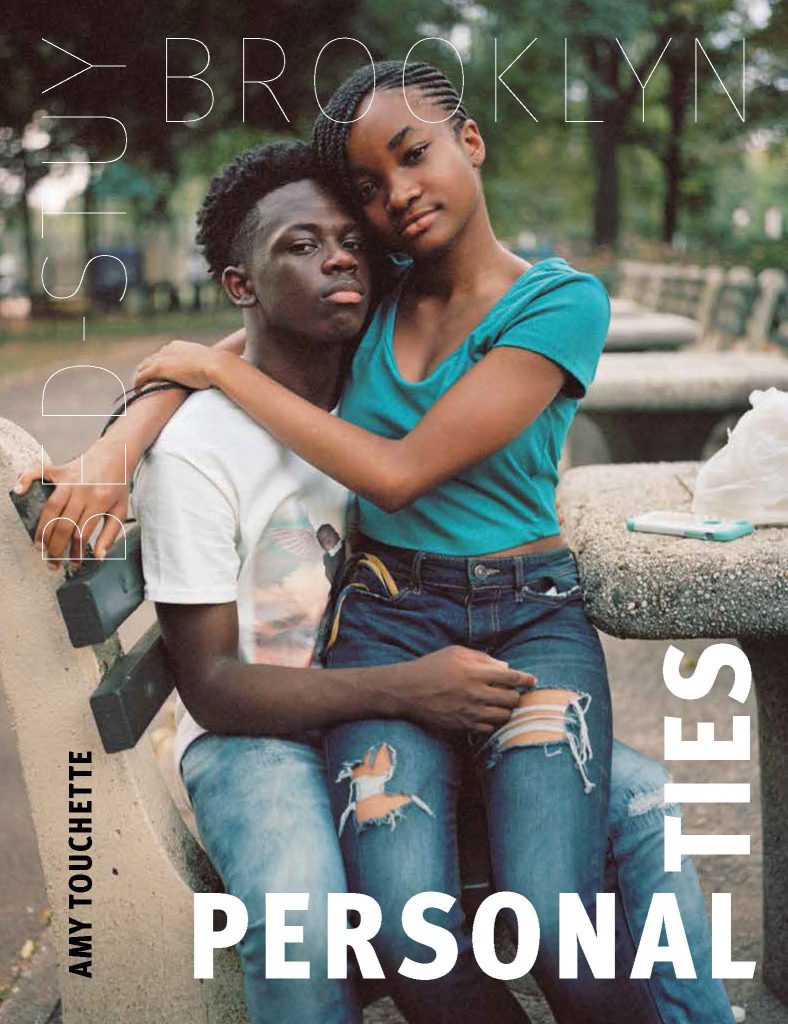

Ann Napolitano is the author of the New York Times bestseller, Dear Edward. The book was adapted into film series on Apple TV+. In addition, she has authored, A Good Hard Look and Within Arm’s Reach. Hello Beautiful is Napolitano’s fourth published novel and Oprah Winfrey’s 100th book club selection. Napolitano lives in Park Slope with her husband and two sons.