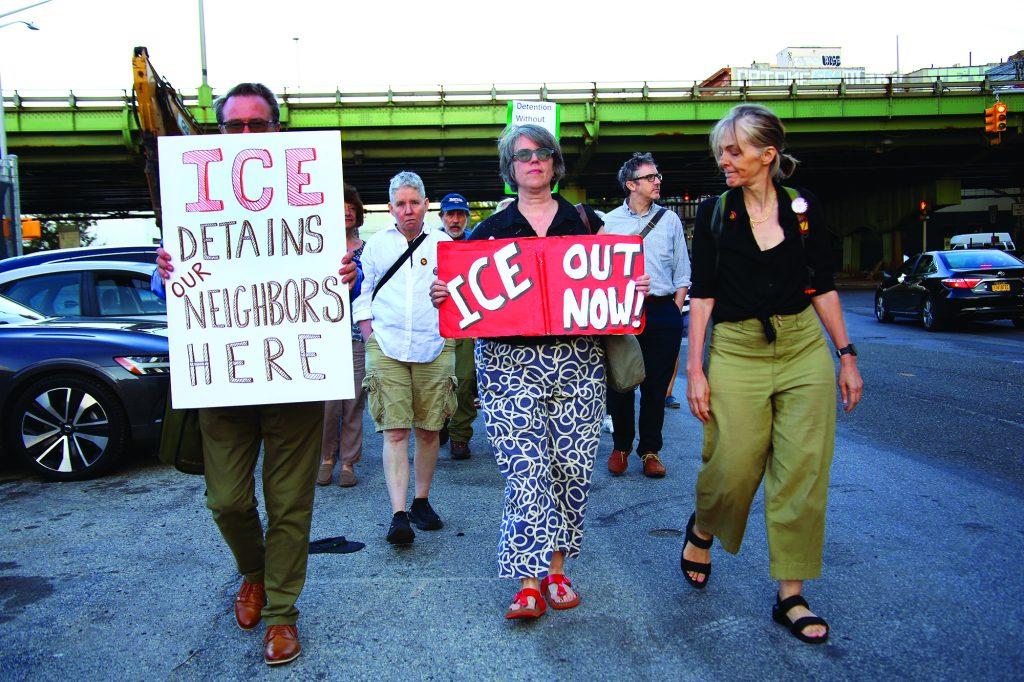

To protest the unjust denial of due process to our immigrant neighbors, a weekly vigil is held outside the MDC. On Tuesdays from 6-7pm, you can find us standing together in opposition to these policies and practices.

If you’ve ever been to Brooklyn’s Costco, you’ve been on, or under, the “Gowanus Expressway”, the elevated portion of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (US Interstate 278) that connects the Belt Parkway, the Verrazano Bridge approach, the Prospect Expressway, and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel approach (No, I will never call it the “Hugh L. Carey” Tunnel).

Whether on or under the Gowanus Expressway, you can’t miss a series of industrial buildings between 29th and 38th Street, along 3rd Avenue. Many of these buildings are now referred to as “Industry City”. Also known as “Bush Terminal”, most of these buildings were designed through an innovative 1895 project of Irving T. Bush, who sought to create a “Great Industrial City within a City”. The project became the largest multi-tenant property for industrial use in the United States at the time.

Industry City/Bush Terminal has had its ups and its downs, like the rest of Brooklyn. Long seen as an area with potential, there was a serious effort to significantly rezone the area in 2017 to include larger retail spaces and hotels. The effort failed due to community concerns that the rezoning would gentrify Sunset Park and displace residents. Today, Industry City is a vibrant creative community including 6 million square feet of industrial, retail and office space.

At the northern end of this neighborhood lies a building complex unlike the others, the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC), located at 80 29th Street. The MDC was built in the 1990s, and is under the control of the United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons. Two former Bush Terminal buildings previously located on the site were demolished in spectacular fashion in 1993 to make way for the current structure. The MDC was built to hold up to 1000 federal inmates, mostly in bunk-bedded cells for two, largely awaiting criminal proceedings at New York City federal court buildings. The MDC detains more inmates than over 75% of other federal prisons across the country.

When the MDC was built, it wasn’t the only such facility in NYC. The smaller, overcrowded, Metropolitan Correction Center (MCC) in Manhattan was also in use. However, after the notorious 2019 death of Jeffrey Epstein in the MCC, the facility closed in 2021. Some of the Brooklyn MDC’s most infamous detainees have included: Ghislaine Maxwell, R. Kelly, “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli, fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried, Luigi Mangione and most recently, Sean “Diddy” Combs. Most MDC inmates are held for non-violent crimes, like drug trafficking, immigration violations, and fraud.

Like the MCC, the Brooklyn MDC regularly holds significantly more detainees than the building’s planned capacity. As a result, the conditions at the MDC have long been consistently considered outrageous. A group of Muslim, Arab, and South Asian male non-citizens settled a 2006 lawsuit against the federal government due to the horrendous conditions of their confinement. The men were rounded up through racist anti-terrorism actions after 9/11 and confined to the MDC. While at the MDC, they experienced excessively prolonged detention, were abused physically and verbally, and subjected to arbitrary and abusive strip searches.

A former warden called out the MDC as probably the most troubled facility under the control of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The warden’s comments came shortly after a week in January 2019 when the MDC lost heat and power after an electrical fire. MDC inmates could be heard outside the facility banging on the walls and windows in desperation. During planned maintenance in 2021, power and water were shut off for four days. As a result, inmates’ toilets were reportedly overflowing. Even when the power is functional, roaches and maggots are found in the food, mold is rampant in the bathrooms, and exposed wires are within reach.

In 2016, the National Association of Judges, Women in Prison Committee, authored a report specific to conditions in the women’s quarters of the MDC. Four federal judges who visited the facility on multiple occasions reported that over 150 women were being held in two separate large rooms, each with rows of bunk beds on one side of the room, toilets and showers on the other side of the room, and fixed tables in the middle; there are no windows in these rooms, so there is no fresh air or sunlight. Air conditioning is generally not available in any housing units in the complex. The women were confined to these rooms throughout their detention, with no opportunity for outside exercise. The exercise that the female inmates were offered was in a deficient space with a handful of stationary bikes, and limited other equipment.

The MDC is known for frequent “lockdowns”, where inmates are confined to their cells for long periods of time. Lockdowns became more commonplace during the COVID 19 pandemic. Recent justification for lockdown conditions is the endemic understaffing of the facility, with 30-55% of staff positions unfilled at any given time. Lockdowns have been known to last for weeks, during which inmates get a maximum of 2 hours outside of their cells per day. Inmates have claimed that during lockdowns they only get 15 minutes outside of their cells every three days, just to shower. These conditions result in physiological and psychological distress, with long lasting consequences for inmates.

MDC leadership has been berated by federal judges for failing to provide adequate medical and psychological care to detainees. One federal judge ordered an inmate with a MRSA infection to be transferred to a hospital, but the MDC staff placed the inmate in solitary confinement instead, later claiming it was an error. In another case, staff failed to provide an inmate with required medication after an appendectomy, and then lied about it. The emergency call buttons are often broken, resulting in one inmate having a diabetic episode being tended to by his cellmate overnight, until an officer made the rounds and called for medical intervention.

Violence between detainees and with staff at the MDC is terrifying. Since 2020, 17 inmates have died due to violence at the MDC. Stabbings and beatings are common, even though the vast majority of inmates have no history of violence before detention. When you think about the lockdowns and other deplorable conditions, the psychological consequences of such trauma will inevitably lead to violence.

Corruption amongst facility staff is also prevalent. At least 6 former MDC staff members have been charged with federal crimes for smuggling drugs and other contraband into the facility.

Confinement at the MDC, near the federal courts, should make access to legal assistance easier. However, due to lockdowns and staffing shortages, access to legal representation for inmates held in the facility is actually limited. Shortly after the 2019 power outage, the Federal Defenders of New York, a non-profit legal organization who represent indigent clients in New York’s federal courts, filed a lawsuit claiming that the MDC policies and practices violated their clients’ constitutional and state rights to an attorney. The case is still pending in mediation six years later.

In 2024, a federal judge publicly refused to send an elderly defendant to the MDC, calling the conditions “dreadful”. Many other federal judges have gone on record making it clear that their sentencing decisions are based in part on the goal of not sending people to the MDC for any period of time longer than absolutely necessary, if at all.

The problems at the MDC have spanned Democratic and Republican presidential administrations. In July 2024, President Biden signed the Federal Prison Oversight Act, which aimed to increase transparency and accountability within the federal prison system to address long-standing problems. There was hope that conditions at the MDC, and sites with similar problems, would improve as a result. And then came Donald Trump’s second term which started in January 2025.

On March 27, 2025, President Trump signed an Executive Order that effectively ended collective bargaining for federal employees, including those of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. This order canceled the existing correctional officer agreement, and rescinded the efforts underway to incentivize new staff hiring.

Then in the summer of 2025, the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) unit of the Department of Homeland Security started detaining around 100 immigrants at the MDC. With grave concerns for the safety of the detainees, Congressmembers Dan Goldman (NY-10), Congressional Hispanic Caucus Chairman Adriano Espaillat (NY-13), and Nydia Velázquez (NY-07) sought entry to the MDC and were denied. Members of the Democratic Congressional delegation have filed suit against the federal government for denying them access to the MDC and similar facilities, including “Alligator Alcatraz” in Ochopee, Florida. Denial of access to members of Congress is in direct contradiction to federal policies and court decisions that have clearly provided these policy makers the right to access these facilities for oversight purposes. Alligator Alcatraz seems so far away. The MDC is too close for comfort.

While the MDC is run by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and staffed by federal employees, 90% of ICE detention centers are privately owned and operated by for-profit corporations. American tax dollars are being spent to support the profits of private individuals on the backs of inmates being held in deplorable conditions.

I have been aware of the MDC’s presence for decades. I think I’ve heard about these concerns for MDC conditions before. To be honest, these concerns didn’t become real to me until I found out that ICE was using the MDC to detain our immigrant neighbors.

The MDC has long detained immigrants involved in federal criminal action for immigration law violations, including “unlawful entry”, “failure to depart” and “marriage fraud”. The latest round of ICE detentions, however, do not involve federal criminal court action, or accusations of criminal liability. More than 70% of current ICE detainees across the country don’t have a criminal record. And of the detainees with a criminal record, many were convicted of non-violent misdemeanors.

ICE is performing harrowing workplace raids, including right here in Park Slope, and across our Sanctuary City. Shielding their faces by wearing masks, not wearing uniforms, and refusing to provide evidence of legal authority for their actions, ICE agents leading these raids aim to terrorize and traumatize immigrant communities. ICE is currently detaining immigrants as they report to immigration courts in pursuit of civil legal actions that would provide or maintain them with a status that allows them to remain in the United States, at least for the duration of proceedings on the merits of their cases. Immigrants lawfully seeking asylum are showing up for their day in court, only to have the federal government close their cases, so that ICE can detain them for not having a pending status.

Earlier this year, former Park Slope City Councilmember, now NYC Comptroller, Brad Lander, was arrested for allegedly “impeding a federal officer” at Manhattan’s Federal Plaza, as he attempted to protect the rights of an immigrant being detained after such an appearance. The charges against Lander were later dropped.

In some cases, ICE has detained immigrants with pending immigration court cases that should provide them protection from detention and deportation. There are also cases where ICE has unjustly detained green card holders, with permanent resident standing. Even when immigrants have been later released from ICE custody back into their communities, the damage is done.

To protest the unjust denial of due process to our immigrant neighbors, a weekly vigil is held outside the MDC. On Tuesdays from 6-7pm, you can find us standing together in opposition to these policies and practices. Just this week, as our vigil was ending, a mother and her teenage son emerged from the facility after trying unsuccessfully to locate her older son. Speaking primarily in Spanish, she asked us for help. Her son has been held for weeks, and she has not been able to see him or talk to him. She is worried because she has heard how bad the conditions are in the MDC; she has heard that inmates die there. Members of our group connected her to appropriate legal services. Neighbors are supposed to support neighbors.

If you’ve ever been to Brooklyn’s Costco or visited Industry City, you have seen the MDC, and probably didn’t even know it. As you were bargain shopping in bulk or supporting local Brooklyn businesses, over a thousand of your neighbors were being held, many unjustly, just a few blocks away, in appalling conditions. Now that you know, what are you going to do about it? q