My family was born of a showmance. My husband, David, and I met starring opposite each other in a college play in which I played Bonnie, the exotic dancer, and he played Phil, the depressive alcoholic who threw Bonnie from a moving car. Isn’t that how all great love stories start?

David and I were Theater Kids. Correction; we are Theater Kids. Because when you are really, a genuine-article Theater Kid, you are one for life. In this way, and this way only, being a Theater Kid is like being the President.

I knew with certainty that David and I were Theater Kids a few years ago on a road trip when David put on the soundtrack to Miss Saigon, the musical that caused me to weep like a newborn babe being delivered when I saw it on Broadway for my 16th birthday. I hadn’t heard the opening song, “The Heat is On in Saigon,” in two and half decades and I realized two things:

1. My memory of the lyrics as heart-wrenchingly poetic might be euphoric recall. Case in point: “This stink is making me choke/ Turns out this war is a joke/ Turns out the joke is on you-oo-oo-oo!”

2. The questionable quality of the lyrics notwithstanding, my heart swelled with emotion as I sang Every. Single. Word. Not just the chorus and the verses, but the little interjections the soldiers and the ladies of the night exclaim to each other, all of which I remembered verbatim. When I sang, “How are you doing there, John?” and David replied, without missing a beat, “I’ve got the hots for Yvonne!” I understood that David did too.

And that, dear readers, is how you know you are a Theater Kid.

It will come as no surprise that all three of my children have turned out to be performers. The oldest two inhabit that theater-adjacent world of music, and are singer/ songwriters. There’s a lot of overlap between the two worlds, the main difference being, as far as I can tell, the props. In lieu of highlighted scripts, singer/ songwriters always have a guitar within easy reach, and a robust supply of capos. Then, too, there’s the fact that while singer/ songwriters often collaborate with other musicians, they tend to feel most at home on a single, solitary, spot-lit stool whereas theater kids yearn to join a cast of characters.

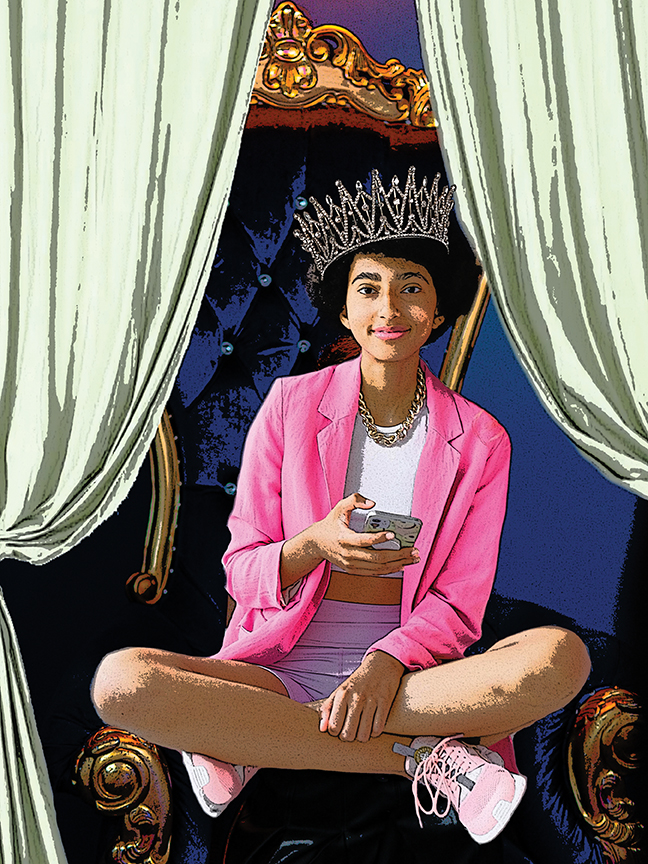

It’s too early to tell for sure but it looks as though our youngest, known in these parts as Terza, may have inherited her parents’ penchant for the theater. Now thirteen, the kid’s been singing and dancing and performing high-stakes, improvised dramatic monologues since she learned how to operate an Iphone. She’s never met a stage she didn’t fling herself onto.

She did musical theater after-school programs throughout elementary school, even during the Covid shutdown. If you thought watching Hamilton performed by 3rd graders was difficult to get through, imagine Hamilton performed by 3rd graders on Zoom. As an avant-guard piece of performance art, it would have been thought-provoking, particularly the endless parade of siblings wandering accidentally onto the “stage” of the Zoom screen, some not dressed for public viewing. A young actor in his dad’s dress-shirt and suit vest yelling, “MOM, GET OUT! I’M IN THE MIDDLE OF MY PLAY RIGHT NOW!” was a moment of high drama which sadly upstaged Terza’s rousing rendition of “What Did I Miss?” as Lafayette.

Thankfully, by the time Terza entered middle school — the stage of life during which most Theater Kids’ resumes truly begin — Covid had receded. Her first middle school play, Matilda Jr was performed in a real school auditorium, where all the revolting children could pump their fists into the air, Che-Guevara-style, and belt their hearts out, sans masks, to in-person applause.

Terza played the role of a School Kid #5, providing David and I the chance to dust off our “there are no small parts, only small actors” speech. We were worried she might find it tedious, all those many months of long rehearsals with so few lines, but we’d forgotten about the magic sauce that makes all the tedium worth it, the alchemy by which a group that begins as twenty separate kids becomes one family – a big, loud, spotlight-seeking, microphone-hogging, over-the-top, marvelously hyperactive, joke-cracking, ballad-singing, pirouette-turning, tight-knit, til-the-wheels-come-off family. It’s what keeps Theater Kids coming back for more.

When Terza came back for more in seventh grade, she got a lead role, starring as Puck in her school’s adaptation of Midsummer Night’s Dream. This gave David and I the chance to dust off our “on the merits of paying your dues” speech, brimming with applicability to various life situations.

As the weeks of rehearsal went on, I marveled that, though there usually doesn’t seem like a shred of overlap between my childhood and my kids,’ defined by technology and all its wonders and ills, in the tiny little world of Theater Kids, little has changed. Of course, it makes sense when you stop to recall that theater is an ancient art form.

I bet the ancient Greeks rehearsing for Oedipus Rex warmed up with “me-may-ma-moh-mooooos.” grumbled about tech week, and chirped back to the stage manager, “Thank you 5!” with giddy professionalism. I bet they felt the same inimitable mix of terror and thrill when they first stepped onto the stage, the same electric crackle at the first laugh, the same sense of delightful disassociation when they lost themselves in a character and relationships and problems that were not theirs. I bet their hearts were pounding in just the same way when they joined hands to take a bow, and I bet on closing night, they hugged each other tightly and wished it wasn’t over quite yet.

Though I didn’t realize it when I was a preteen actor, I see now that theater offers exactly what middle schoolers so desperately need: At a time in your life when you’re wrestling with identity, you get a chance to just fully become someone else for a little while, to take for a spin an entirely different personality and life story. At a time when you’re scrambling to find your footing in an ever-shifting landscape of uneven terrain, where the weather is treacherous, and unpredictable — hailstorms in July! deadly winter heat waves! — you find a sure spot, a safe spot protected from the elements, a big strong tent filled with other travelers. Here, there’s community and acceptance and play and laughter and a break from the fray. It’s just what’s needed.

I can imagine a future, twenty five years hence, where Terza will be driving her flying car with a couple of rugrats in the back seat, and someone will mention Matilda the musical. Terza will cue up the soundtrack on whatever future AI brain-chip people will use to play media. She’ll sing: “We are revolting children! Living in revolting times!” She’ll remember every single word