Editor’s Note:

When my editor asked me to write about my experiences living in Brooklyn, when the novel coronavirus first hit the city— and then my subsequent move to Southern California, just as the virus and the wildfires were beginning their assaults here— I obliged, without hesitation. I had moved to the Los Angeles area over the summer, right as NYC’s economy was reopening and mass protests against police violence were sweeping the country. California was great at first; the mountains and ocean provided a likely source of comfort, and COVID-19 cases were on the decline. But then the fires happened, and then the infection rate skyrocketed, and suddenly we were back to a partial shutdown with more forced isolation. It felt all too familiar to life in NYC last spring.

Writing about the events of the past year has been a catharsis for me. I look back at the photos of empty park benches and deserted streets with a deep appreciation for the beauty of the city and the resilience of New Yorkers. Those were difficult months and some facets, like the makeshift trailer cemetery in Sunset Park, will haunt me for a long time. But like my friend Jen said, after the wildfires finally quelled, “Nature has an incredible way of healing and rebounding.” I think the same is true of people.

It was Monday, March 9, 2020, and I was sitting in the basement of the printshop scrolling through emails and news updates on my iPhone. Ink covered my fingertips and stained my skin. I didn’t care. I was still reveling in nostalgia from the weekend. It was one of the best weekends of my life. It sounds cliché, but it’s the truth. I lived for the New York art fairs! The Armory Show, SPRING/BREAK, VOLTA, Moving Image— I looked forward to the spring shows every year. The day before, I toured Art on Paper at Pier 36 in the LES. A friend had given me VIP tickets.

I met up with friends later in the afternoon. We drank coffee and walked along the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. We discussed the art world, our pets, our families, and our careers. We joked about our exes and thought about the nuances of life. It was sunny and warm for a New York day in early March. I held their baby close to my chest as we walked. I was entirely ignorant of her world and to how soon the scope of her world— and our world— would change.

“Fuck,” I mouthed to myself. BREAKING NEWS: Several East Coast Universities Cancel Classes in Coronavirus Response. I put my phone down on my lap and buried my face in my ink-stained hands.

The printshop smelled of paint thinners and chemicals. The air was dank. I was starting to feel nauseated from the fumes. What did it mean that colleges all around the city were canceling classes? Was this the beginning of a lockdown? No, they’re just following protocol, I thought. This is temporary.

I stood up to stretch, and to get back to work. I put my phone in my back pocket and headed up the stairs. At that moment, my phone vibrated with a text message from my husband, Matthew:

“Our lab is closing, indefinitely. I have an hour to pack up my office and leave the building.”

Indefinitely sounded exaggerated. I was sure he meant a week or two—at least I had hoped it wouldn’t be longer than that. Our apartment was already crowded enough.

I looked around the printshop, suddenly aware of how quiet it was. Everyone had gone home for the day. It occurred to me that maybe the printshop would also close. In which case, I would have to call my students to postpone our sessions for a few weeks. Maybe I should head home, I thought. My throat was itchy and I had developed a mild cough, on top of chemically-provoked nausea. Allergies. Yes, that is it—allergies. I always get a bit of a cough when the seasons change.

Later that night, I texted my cousins to ask if anyone had heard from our extended family in Bari, Italy.

Two days later, I noticed my cough was getting worse. It was allergies— and maybe stress. I had convinced myself of that.

“Julia, you should really call your doctor,” said my friend with the baby.

My dog and I were walking around Prospect Park when she called. I was happy to hear her voice, despite her concerns about my health. Should I call my doctor? No, I’m fine, I thought. I’ll pick up cough syrup in the morning. Maybe if I tell her I’m drinking cough syrup then she’ll stop worrying about me.

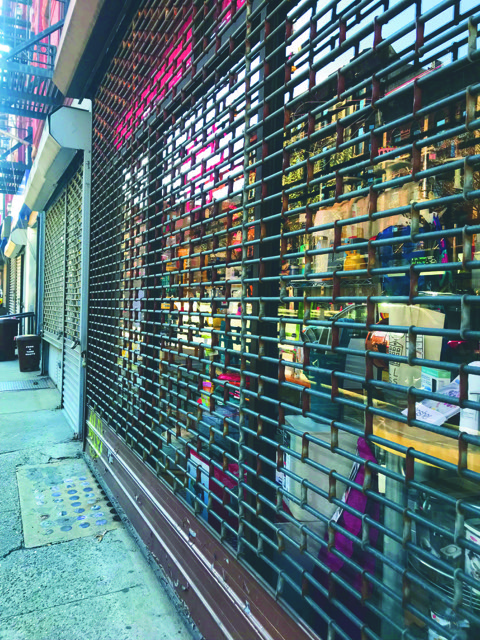

The next day I walked to the bodega on 8th Avenue and asked the owner if she had any cough syrup. I was too focused on her breath to hear her words. I could feel it circle in the air. I pictured infected and microscopic droplets touching my face. My heart began to race as the panic set in. I stepped back, thanked her anyway, and wished her a good day. I’ve always liked her.

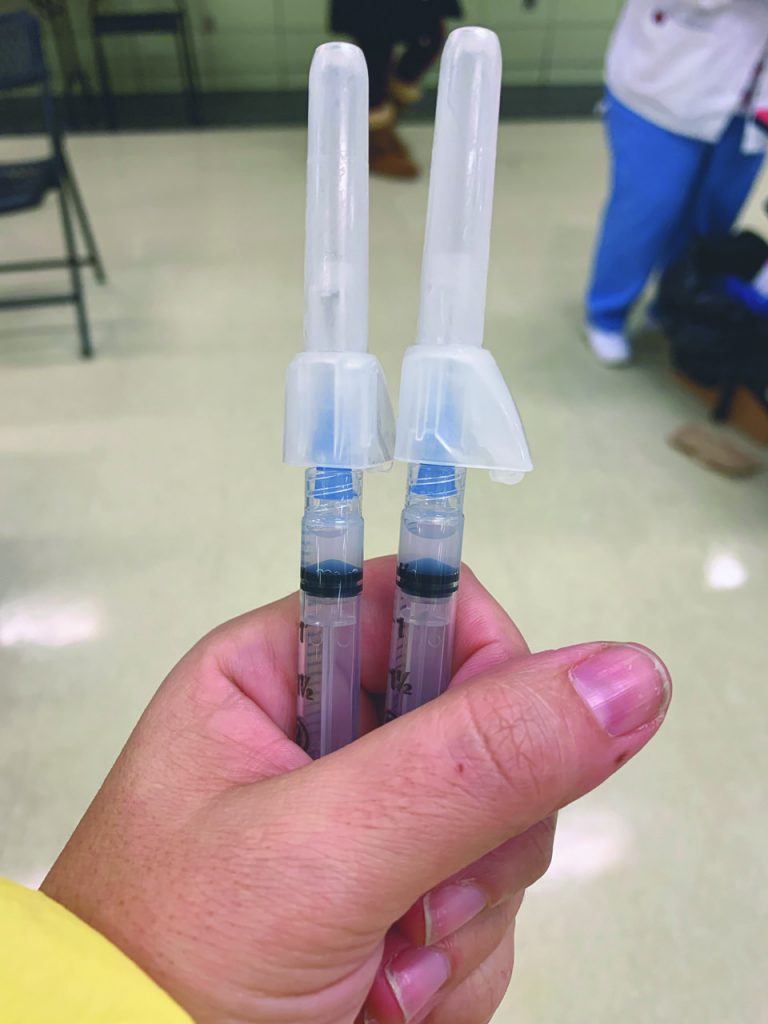

I called my doctor from the corner of 7th Ave., outside of the fourth bodega of the day. I assured him I didn’t have COVID but I really needed cough syrup. I couldn’t find it anywhere. The hoarders of Park Slope had planned for this. He addressed me gently as if I were about to receive life-altering news. He ignored my self-diagnosis of allergies and recommended that I pick up the prescriptions immediately and take them as directed until the bottles ran out. He also suggested that I self-quarantine and use an inhaler—“just in case.” We both knew that getting a COVID test was a nearly impossible feat.

The next day, word got around that some of my colleagues were sick with COVID-like symptoms. It’s a good thing I was laid off, I thought. Matthew and I were going over our finances. I could tell he was stressed. He assured me his job was secure but I was skeptical. We both knew that my loss of income would drain our savings. In times of skepticism and uncertainty, I’ve found that it’s helpful to make lists of gratitudes and to recite them as mantras.

We are safe. We are healthy. We are blessed.

New worries involving probable state mandates and rumors of forced isolation began to culminate in the media. Fears of de Blasio shuttering the bridges and quarantining the city were circulating and had reached the ears of most New Yorkers. Upon learning this news, Matthew decided we should shelter in place with his family, in a small suburb north of Boston. We would share his mother’s one-bedroom apartment. He decided that we would sleep on the floor, and I would work on my art in her living room.

I refused. Brooklyn was my home. If the virus was going to ravage and decimate the city for a few weeks, or maybe a month, I would be there to see it through. This couldn’t last forever, could it?

The disagreement continued for hours.

Cigarette butts began to collect in a defaced olive jar on our back porch. Throughout the week, I reminded Matthew that the CDC recognized smokers as “high-risk” and vulnerable to respiratory illnesses. “You really need to take Chantix,” I said.

My friend with the baby told me to go easy on him. “This is a stressful time for everyone,” she said.

I had convinced myself that this was all temporary. I would take this time to work in my studio and continue developing my visual arts practice. If I am forced to stay in Brooklyn, I should at least be productive, I thought. This can’t last forever. I will be back at work soon enough.

That day I sat in my studio, surrounded by my work, and cried. My art, which is largely autobiographical, was not important. People were dying.

The laundromat that I had used regularly for two years was closed. I worried about the owners, two brothers. I hoped they had closed for personal reasons unrelated to the pandemic. Our Federal Government has failed to protect essential workers, I thought.

. . .

It was April 12, Easter Sunday. This day means everything to my family but nothing to me. I walked home from my art studio, up to 18th street to 7th Ave. A cop rode past on a motorcycle, slowing down at the four-way stop. He flashed his lights to stop the cars approaching him. Behind him was a black Cadillac hearse with a purple flag that read funeral. There was no congregation of mourning family; no church bells; no priest. The body would likely be buried alone. I wondered if the unlucky person passed away in isolation. I imagined that the body inside of the hearse belonged to an older man— a man with a bald head and a full beard. I prayed for his soul to reach others, somewhere in another realm, far away from Brooklyn.

I called my Dad to wish him a Happy Easter and to tell him that I missed him. Physically, I was healthy, somehow, but mentally, I was slowly falling apart. The isolation, the economic fallout, the burials on Hart Island, the nonstop news updates— COVID was consuming all of my time. It was the first thing I read about in the mornings and the last thing I would consider at night. I was hardly sleeping in those days. Small moments of solitude were infamously interrupted by the sounds of ambulance sirens.

“Dad, can you hear that?” I asked. The NYPD was looping around the park with a megaphone, blasting prerecorded messages at park-goers to “wear a mask” and “stay at a six-foot distance.”

“This feels like… Communism,” I said. As soon as the word Communism rolled off my tongue, I regretted it.

“This is not what Communism is like,” said my Dad, apathetic to my misery and inherent privilege. He reminded me that his parents and siblings lived through the Mussolini regime in Bari. My dad was born a year after the war ended. “You kids have it so much better than we did.”

A month later, police officers arrested a young Black mother at the Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center Station for not wearing her mask properly. The encounter ended in a violent assault.

We gave our landlord a 30-day notice on May 1st. Our lease was up and he refused to let us continue renting month-to-month, despite the city’s high-infection rate and the eviction moratorium. Maybe this will be good for us, I thought. Matthew had accepted a job offer in Southern California.

. . .

The 7:00 pm cheers for medical frontlines and essential workers kept me going. I looked forward to them every night and made an effort not to miss them. But tonight I was cheering quietly. I was carrying home groceries and didn’t want the bags to touch the ground. I listened to the sounds of applause, and the car horns, and the homemade instruments, while consequently walking past the trailer morgues on 7th Ave. Holding my breath, I peered through the gate. The morgue workers were outside. This can only mean one thing, I thought.

I don’t think I will ever be able to expunge the horror that the images of those trucks brought to the city or me personally. Coming back from that hellscape seemed [and sometimes, still seems] unimaginable.

It was the end of May and the moving truck had come and gone. We cuddled up in blankets and sleeping bags on the hardwood floor of our apartment. The sounds of police sirens were aggressive, and we heard helicopters circling overhead. We knew they were headed towards Barclays. We laid awake in silence for most of the night. I prayed for the safety of the protestors.

The next morning we packed up our Jeep and left the city. The dogs were in the back, wedged between suitcases and sleeping bags. We drove over the Verrazano Bridge to Staten Island and through Jersey. I thought about the past few months and all of the loss the city endured. It would take time, maybe years, but the city would heal. Nature has a way of rebounding after wildfires devastate the land; and so would NYC. I would miss Brooklyn and the life I had created, but I was eager to get to California. The state’s economy was in the early stages of reopening and the infection rate in Los Angeles was on the decline.

Los Angeles has a great art scene, I thought. How delightful it was to be so naïve.