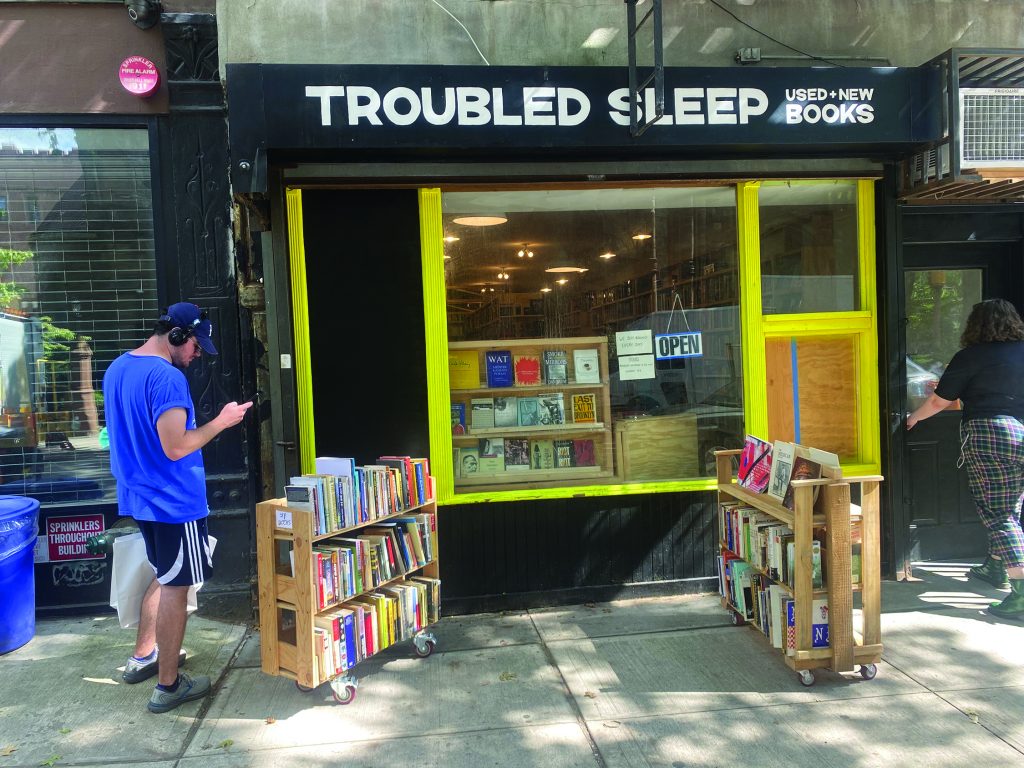

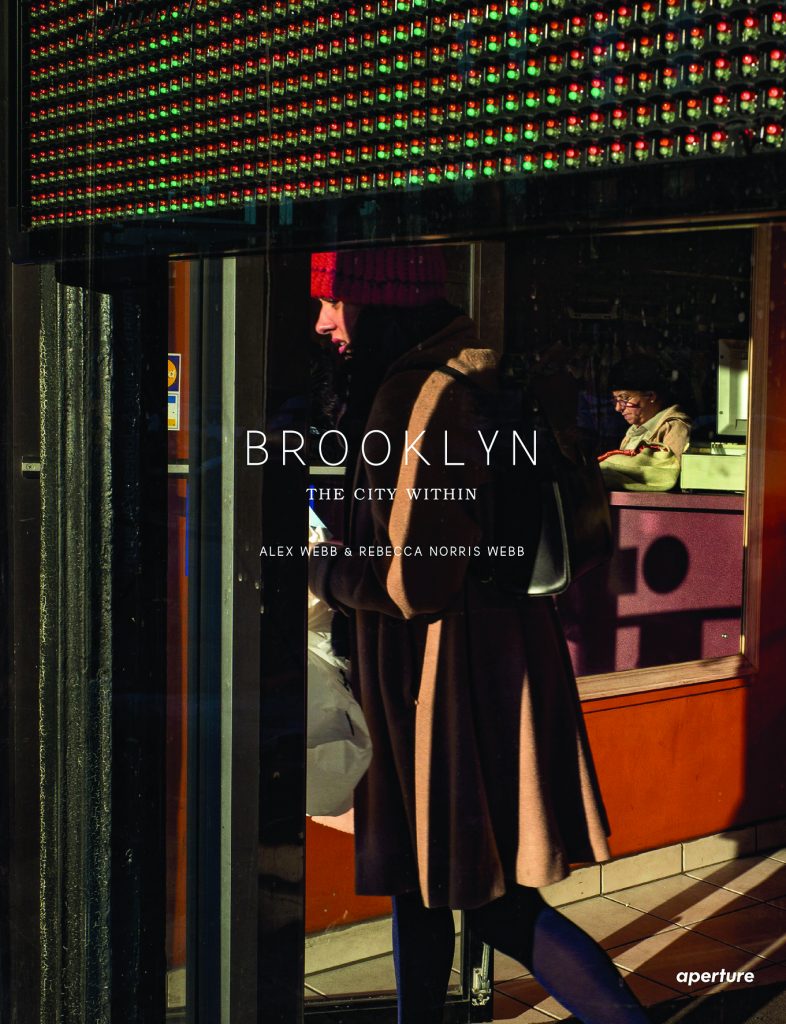

It’s Portlandia’s Women and Women First but this one seems a bit more pink, a lot more inclusive, and all about love and community.

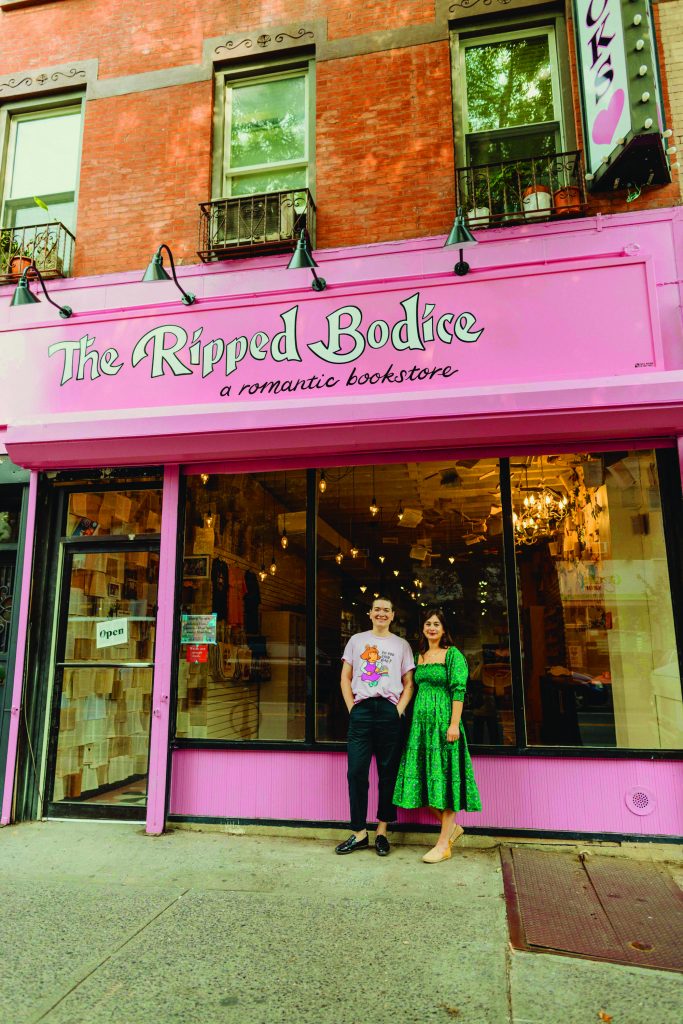

By now you’ve heard about them, read about them, joined one of their book clubs, or at least been stopped in your tracks by our lovely new pink neighbor on 5th Avenue. The Ripped Bodice is the talk of the Slope.

Lucky me, after all the wonderful and well-deserved press that sisters and co-owners Leah and Bea Koch have already received, Leah agreed to sit down with me for an interview. And for my Park Slope Reader debut!

Landing in step with the likes of Barbie, Heartstopper, and The Summer I Turned Pretty, there was a line down the block awaiting the grand opening of their Park Slope location on August 5th. Their opening day featured a book signing by Casey McQuiston, author of Red, White and Royal Blue, just five days before the movie based on it was released. These sisters know when to pounce on opportunities.

“It was an idea we came up with and believed in and just went full speed ahead with. I don’t really wait for anything,” Leah told me with a laugh. The sisters were 23 and 25 when they launched their first store in Los Angeles.

“When you have an idea that you think no one else has thought of, it’s for one of two reasons. One, it’s not a good idea. Or two, this is a huge hole and I’m going to be the one to fill it. We went with option number two.”

The Koch sisters opened the first romance-only bookstore in the United States, and their idea caught on. Since they opened their first store in LA in 2016, more romance bookstores have popped up around the country, and they have found community with one another. “It’s a tiny network literally 10 people,” Leah counted them on her fingers. They’re all in touch, and each new store has reached out to the trailblazing Koch sisters who are excited about the growth of romance bookstores in the US.It’s a beautiful network of women supporting women.

As for choosing Park Slope for their second location, it just made sense. Their family is here and growing! Leah moved here to run the Park Slope location, while Bea runs the original LA store.

“To be honest, THIS is why we moved to Park Slope.” Leah held up her phone for me to see the background. Her nephews, Mo (3 ½ years) and Saul (7 months).

Bookstore culture and the importance of reading was woven into the sisters’ lives from early on. Trips to local bookstores were a Sunday afternoon treat in their family.

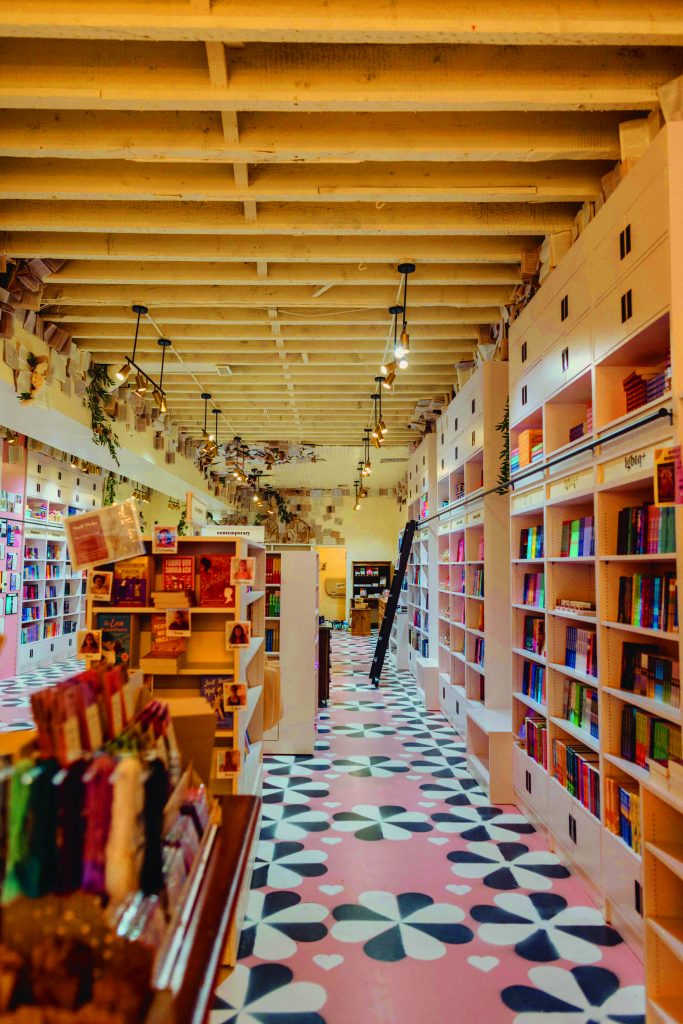

“Our parents encouraged us to read a lot but also spent a lot of time emphasizing how vital bookstores are to communities”. That sentiment is palpable inside The Ripped Bodice, which has been transformed from a pet supply store into a truly whimsical, welcoming space.

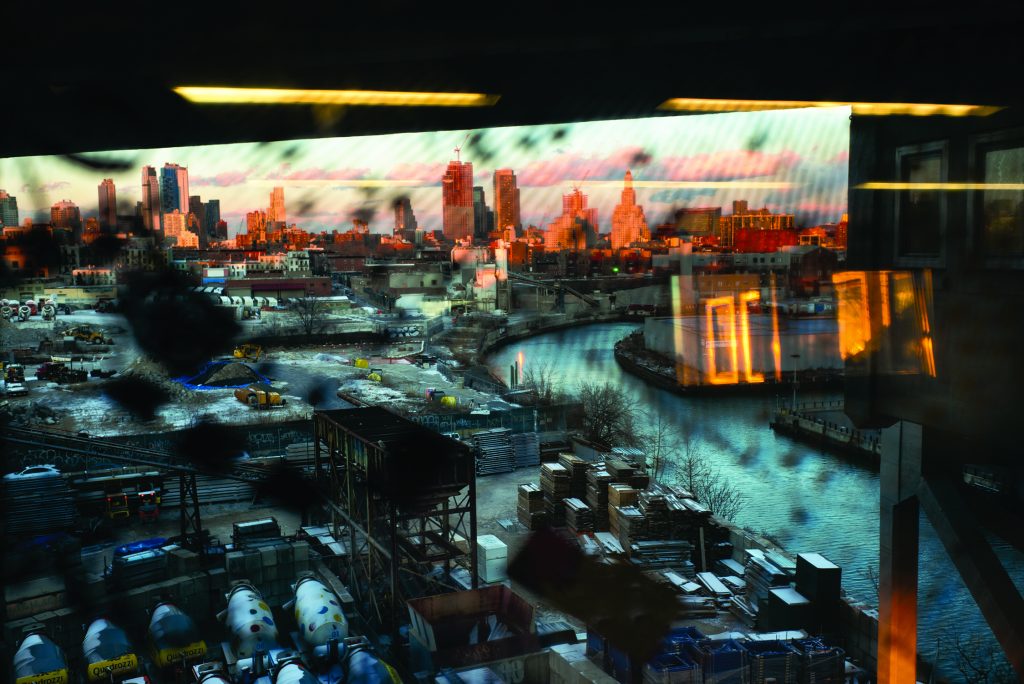

Aided by her degree in Visual and Performing Arts Studies, Leah performed the renovations herself. She documents the process on TikTok which earned her a huge following before the store even opened its doors. Artistry and passion have been etched into every corner, and the patrons can feel it. Many have mentioned spending more time in the store than they would have anticipated due to the environment Leah has carefully created.

“I wanted to be a production designer, and now I’ve designed my own stores.” Manifestation, baby!

They also take pride in asking their readers the right questions to find the books they’ll enjoy the most. In fact, Leah helped me pick out three books during our interview.

Their reach extends far beyond their local patrons and fellow romance bookstore owners. They’ve gained fandom from all over the country, including romance novelist and former Georgia State Representative Stacey Abrams, who has been a patron and fan and since their beginnings in LA. In 2017, Abrams tweeted a shoutout to The Ripped Bodice and they are now “internet pals”.

“We literally got the tweet printed on a t-shirt.” Leah emphasized the impact Abrams had on their business. Small favors from people with influential platforms go a long way for small, family-run shops. They have since hosted twitter Q&As together, hosted fundraisers, and participated in a project that raised nearly $500k for Abrams’ 2018 gubernational campaign.

The Koch sisters admired that Abrams was so proud of her career as a romance novelist during her election, despite criticism. Many of her opponents attacked her romance novels and writing in general, focusing on what they saw as trivial pursuits despite her extensive law career and years serving as a member of the Georgia General Assembly.

Abrams’ unabashed love of the romance genre mirrors the identity of The Ripped Bodice. The genre has historically been painted with a trivial or salacious lens, which has caused many readers to feel a sense of shame for their interests. The psychological pink tax of literature. Leah blames this on the misogyny and sexism still prevalent today.

“We are doing a better job of interrogating our own internal biases, and other people’s as well. We’re not born thinking romance novels are dumb.” She points to Gen-Z for making progress towards doing away with romance genre shame. As she put it, “Any 19- year- old is thinking, Why would I care about anyone else’s opinion of what I’m reading!”. And that wisdom is catching on, too.

A “bodice ripper” is an outdated term for sexually explicit historical romance novels. Some readers are offended by the term and even see it as a slur, albeit “a slur against an inanimate object”, as Leah candidly put it. While you can certainly find bodice rippers at The Ripped Bodice, they have a lot more to offer, and the store leans more family-friendly than erotic.

“There is so much power in reclaiming language, especially in a loving way and a way that acknowledges our history”.

The history of the romance genre, like most, is not without its flaws. Indigenous people have historically been fetishized in romance novels, almost entirely by white writers.

“This genre is not a paragon of perfection, and we shouldn’t gloss over the sins of our past,” Leah admits. She also explained that historically, a publisher’s choices for engaging with a female character’s sexuality were either to have her stay a virgin until marriage or have her be raped. Luckily, the genre has evolved since those days, and from what Leah says, she’s seen a huge difference in just the last 7 years.

The Ripped Bodice is a powerful statement of reclaimed, joyful femininity – in their name, in their industry, and in their community.

Community has been important to them from the get-go. “We just became a part of the rhythm of people’s lives”. Leah beamed as she told me about some of her experiences with their customers turned book clubbers turned friends.

“Someone will come in and tell us about a date they’re going on, then later they tell us they met the parents. Or one of my customers was pregnant when I met her, and now her son is starting 2nd grade!”

They’ve watched their community grow, seen customers become friends, go on dates, fall in love, adopt pets, have kids, land new jobs, and intertwine with one another in really beautiful ways.

One of their LA book club members recently got married with many of her fellow book club members joining the couple at the wedding. Real friendships have been formed through The Ripped Bodice community.

The store has a full calendar of events planned, including book signings, author talks, book club nights, holiday parties, and standup comedy. Their LA store has been producing a standup show for over seven years now, hosted by comedians Jenny Chalikian and Erin Judge. Among Leah’s favorite events was a book talk held by Dr. Emily Nagasoki, director of wellness education at Smith College and author of books Come As You Are and Burnout. Lucky for us, Dr. Nagaski will be visiting the Park Slope location for an event in January to discuss her latest book. Mark your calendars!

And while you’re at it, join one of their book clubs. I’ll see you there.