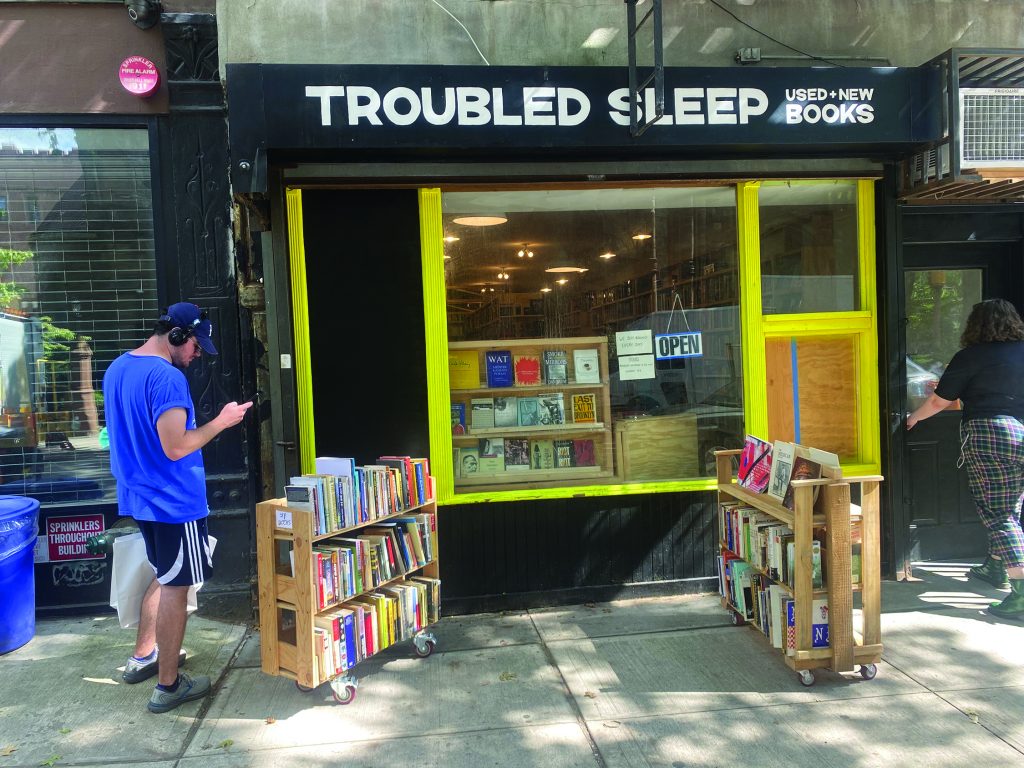

Troubled Sleep aims to reorganize Park Slope’s collection of pre-owned books.

Remarkably, the idea to open a used bookstore in Park Slope was conceived by the founders of Book Thug Nation in only June of this year. Less than six weeks after the idea was casually floated in a meeting, the small book conglomerate opened their newest location, Troubled Sleep at 129 Sixth Avenue, Most recently the home to a neighborhood pet store, the space has been transformed from a muted and easily overlooked storefront into a vibrant, wide-windowed facade. Displayed on both sides of the black and yellow entranceare double-decker carts of used books. Each of them, selling for a dollar.

When I stopped by on a recent afternoon , Alex Brooks was visibly delighted as he rang up a woman with a stack of books held up against her chest, most of which had been selected from the dollar cart. “This is such a terrific find,” Brooks, Troubled Sleep’s manager, said as he flipped through her haul. “Barbara Tuchman might even be one of my favorite historical authors. I’m sad that for many readers, she is considered obscure.” The patron, Donna S, who lives on 8th and Montgomery, agreed. On her way out, she promised to return with decades worth of used books sitting in her house, insisting she’d donate rather than sell.

In Park Slope and surrounding neighborhoods, there are not many used-book stores. There is Unnameable Books on Vanderbilt, and Better Read than Dead in Bed-Stuy, but a signature charm of these stores are the whimsical and chaotic aesthetic of their space. “Used books you can find,” Brooks said when asked what set Troubled Books apart. “But we wanted to take a practical approach to the used-book buying experience.”

This aim speaks to the balance Troubled Books is trying to strike – a bookstore where you can find what you’re looking for and navigate easily, while remaining susceptible to the wide variety of titles you see in between. . About 90% of the store’s books are used. The center display table is reserved for new books, both contemporary and classic. Donna, the stack-carryingcustomer, left with six books. Just one of them was new – Didion’s the White Album – and five used, with bylines like Baldwin, Bentley, and Hemmingway.

While it might seem a bold venture, to open a pre-owned bookstore at the tail end of a pandemic and in the eye of an imaginable recession, the owners of Book Thug Nation are by no means amateur entrepreneurs. Started by four sidewalk booksellers, the group has made a reputation for attracting a wide range of shoppers: collectors of rare works, budding young readers, and everyone in between. Their inaugural store, Book Thug Nation, is a small but formidable used bookstore and literary staple in Williamsburg.

As for Brooks, he, too, is no novice in this world. He has worked with Book Thug Nation for five years:once a loyal customer who caught the attention of the staff with his literary enthusiasm, he was offered the opportunity to help grow the business. Before opening up Troubled Books, he worked at their Manhattan storefront, Codex, on Bleecker Street. Now he is stationed in Park Slope for the foreseeable future, only a few short blocks from where he attended The Berkeley Carrol School 20 years before.

It’s too early to tell If Troubled Sleep is destined for the same success as their sibling locations, which have by now sprouted up all over the world, including cities like Madrid and Valencia. But having walked by several times over the past month, I have yet to see the store without perusing passer-bys looking through – what they may or may not realize – are the bookshelves, quite literally, of their neighbors.