The nice view of the Umpire.

In the past few months, I’ve had some pretty significant realizations about perspective. I don’t often consider subjective interpretations of observable phenomena. However, I’ve come to accept that your physical and emotional perspective can significantly impact WHAT you literally see. Your perspective doesn’t impact what is actually there, or what objectively happens. But, your perspective can influence what you’re looking for, and ultimately can make you sure that you saw something that didn’t even happen.

I, honestly, didn’t realize just how much what I saw could differ so drastically from what others saw, when looking at the same thing. If someone saw something differently from what I saw, I figured they were either wrong, or at least physically seeing things differently. However, my experiences as a new baseball/softball umpire this past spring highlighted how what one sees is influenced by both what they think they’re supposed to see, and also what they want to see. I’ve played and coached these sports for decades, and I’ve witnessed and been a part of my fair share of plays. I assumed that my experienced perspective would help me be a better sports official. I’ve since realized that my coaching and player experience is very different from my perspective as an official, literally and figuratively.

When you’re coaching baseball, softball, or any other sport for that matter, you’re watching the game from one particular perspective, that of a coach. As a baseball or softball coach, in particular, you want to see something specific, especially with a pitch. As a coach, you want to see that pitch within the strike zone without a swing when that pitcher on the mound is your own player. But when the pitcher is not your own player and it’s YOUR batter up at plate, you want to see that pitch out of the strike zone. So, as a coach, you moan or groan at calls you disagree with only when they don’t favor the outcome you seek, and not whether they’re the right or wrong call. Let’s be serious: coaches don’t have any view on a pitched ball to see if it’s actually in the strike zone. Coaches in the dugout or coaching base runners at 1st or 3rd base have absolutely NO perspective to allow for a determination as to whether a pitch has fallen within the approximately 1.4- 2 square foot zone that extends from the batter’s knee caps to their armpits, depending on the rules any particular league is following. When a coach moans and groans about a called pitch, it’s because they didn’t get the outcome they wanted: a called strike if the pitcher is their player, or a called ball if the batter is their player. The coach’s reaction to an umpire’s call is not necessarily related to the reality of where that ball traveled through the air as it reached home plate.

The person with the best perspective on the location of that pitch is the plate umpire, the official behind home plate. The plate umpire is right there. They’ve set themselves up in exactly the right position so that they can see if that pitch crosses the plate or not, and whether the height of the pitch is appropriate to the height and stance of the batter.

You might argue that the batter has a valuable perspective to make a determination about balls and strikes, but they don’t. The batter can’t accurately see if that pitch is a strike or not because the batter’s looking at the ball; they’re not looking at the plate.They actually don’t even see the plate if they’re doing what they’re supposed to do, which is “keeping their eye on the ball”. The batter makes educated guesses about when they should swing and where they should swing based on what they see about the pitcher’s motion and the trajectory of the ball as it comes at them. The batter’s not even really sure of where that ball is in space, unless and until they hit it.

You could argue the pitcher can make a pretty good call on their own pitch. They’ve got an unobstructed view of the plate, after all. But, the pitcher’s perspective has two problems: they’re up to 60.5 feet away from where the ball ultimately ends, and… they have “skin in the game”. That connection to the outcome of the call skews your perspective more than most people will admit.

You might think that the catcher would be the person in the best position to see the pitch and whether it’s a strike or not. They’ve got an unobstructed view of the pitch coming towards them, and are far enough away to see all the contours of home plate. Their head is generally at the level of the strike zone, too. But there are some major concerns circling the mind of the catcher that make them less likely than the umpire to make the right call. The catcher isn’t just observing the pitch, they are working the pitch. The catcher is making rapid decisions on their own effort as the ball is coming at them. They are not just thinking “where is the ball? Did it come in over the plate? To the right or the left? High or low?” The catcher is thinking: “Am I gonna catch this? Am I gonna stop this ball? Am I gonna get hit in the head by a desperate batter swinging their bat with no limited awareness of where the ball is? Am I gonna allow that runner from 3rd base to score if the wildly pitched ball gets past me? And you. Runner on first base. I see you taking a big lead. Take an extra step and I’ll get you out before you can dive back to first.” So, although the catcher is in a great physical location to consider whether or not that pitch is a strike, the catcher is not mentally prepared to make a decision about whether or not that pitch was in the zone. They are pre-occupied by their actual role in the ball game, and their perspective is not objective.

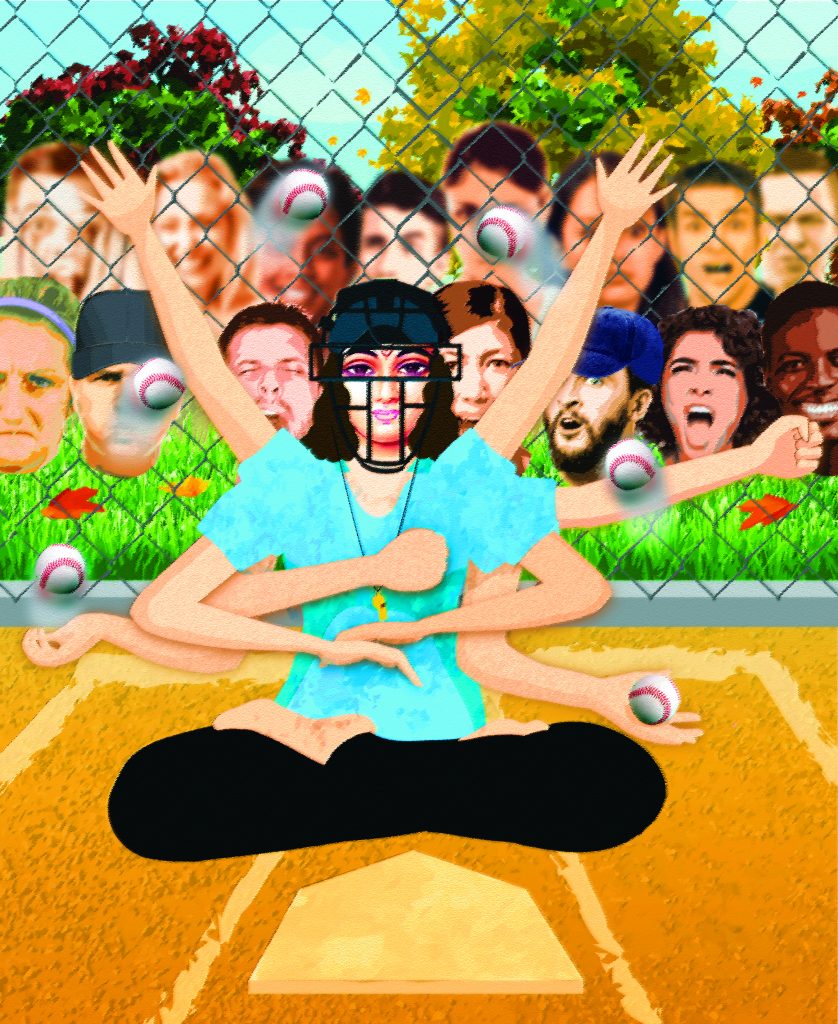

The plate umpire is in the best position, physically and mentally, to make the determination on that pitch, regardless of what the parents in left field foul territory are screaming, or even the parents behind the backstop. Those backstop parents can be the worst. They think because they’re behind the umpire they have the same view. But they don’t. They can’t even see the entire plate from that angle. The umpire, catcher AND batter are all obscuring their view. But, that doesn’t stop them from opening up their mouths and loudly complaining.

When anyone moans or groans about an umpire’s call, it’s usually not because they didn’t didn’t get the call that should have been made based on what they saw; it’s because they didn’t get the call they wanted. And what they think they saw is related to what they wanted, even if it wasn’t actually what happened.

The umpire is in the best position to objectively see that pitch. If the teams have played their cards right the umpire really doesn’t care if the pitch is a strike or a ball because the umpire shouldn’t care who wins or loses. However, when coaches, players and spectators loudly question the umpire’s ability, or visual acumen, the umpire might not feel particularly objective. Umpires are human, and what we see can also be skewed by what we hope to see. So, when people moan and groan at umpires, they’re actually making it less likely that an umpire will be objective on a future call. How’s that for a great reason to shut the heck up?

Umpires don’t just make calls on pitches. They also make calls on plays in the field. Did the ball get caught by a fielder making contact with the base before the runner came in contact with that base? Did the baserunner get tagged? These are usually simple calls, but sometimes they are more difficult than observers would think. Oftentimes, other parties to a play, including baserunners, fielders and even some coaches (but rarely spectators), are in a better position than a plate or field umpire to view the important components of a play. But, just because these players and coaches might have a better literal perspective on the play, they might not actually have the objectivity to see the play clearly.

Fielders, runners and base coaches sometimes might be in a better position than the umpire making the call, because umpires have physical and space limitations. In major league baseball games there are FOUR umpires on the field at any given time, each with a specific role. The umpires work together as a team, but their individual roles are distinct. And, yes, even the most experienced and highly regarded umpires get overruled by video replay technology and appeal processes every once in a while. In almost all of the games I have umpired, I was the only umpire on the field. No team of experts. Just me. A single umpire in that position has to do the job that otherwise takes four people to competently perform.

As the only umpire covering a game, I have to be prepared for many different roles. I position myself behind the plate for most of the game, because that’s where most of my work will be done: calling balls and strikes. When a ball is hit onto the field, or a runner attempts a steal, I have to quickly jump up, remove my mask and find a physical space where I ensure that I have the clearest view on the play that I anticipate I’m going to need to call.

With only one set of eyes, I use my knowledge and experience of the game, along with my expectations of the ability of the players on the field, to determine where I should look. First, I have to look at the trajectory of the batted ball. I have to make a determination of whether the ball was caught, or not, and where in relation to the dimensions of the field the ball contacted a fielder or the ground. At that point, if the ball is still live and in play I have more decisions to make about what to look at.

Should I look at whether the runner who just hit the ball reaches first base before a play is made there? Or, based on where the ball was hit, and the skill of which fielder receives it, should I look at another runner who’s running from 1st, 2nd or 3rd base. I might need to determine whether one or multiple baserunners successfully make it to their next base. Luckily, there’s only one ball on play at any given time, so there is no need to make simultaneous calls on how a ball is played. However, the umpire has to pay attention to other happenings on that field that don’t relate to the ball, at all.

For instance, baserunners are required to touch bases, and the umpire is responsible for observing such contact in case the opposing team appeals that a runner missed a base. Fielders are not allowed to obstruct baserunners in their progress around the bases, and umpires are responsible for recognizing such, and awarding baserunners the appropriate base as a penalty. Sometimes the umpire has to make assumptions about something that has happened on the field, because they can’t possibly witness simultaneous occurrences too far apart to physically observe in the same view. There is a lot going on in the field, and the umpire is expected to know what to look at, and have an objective perspective on everything they see.

In situations when all of the meaningful attention is on one particular interaction on the field involving the ball, a fielder, and a baserunner, the umpire is in the best position, literally and figuratively, to make a call on a close play than any other actors, on and off the field. Players, coaches and fans are likely to be looking at that play subjectively: they are looking for what they want to happen, and, therefore, might see what might not have actually occurred. Umpires are most likely to be looking at what needs to be seen, and to see what actually happens.

In one particular softball game this past spring, all of this crystallized for me. There was a close play on a runner advancing from 2nd to 3rd base on a ground ball. There was no one running from 1st to 2nd base, so there was no force on the play at 3rd base. The fielder could not simply touch the base after securing the ball before the runner arrived to make an out; the runner would need to be tagged by the fielder with the ball in their possession in order to make an out. From the position I took in front of home plate, between the catcher and the pitcher, after the ball passed the pitcher, I had a great view of the runner as they progressed to 3rd base. I could clearly see both relevant fielders: I looked at the shortstop as they received the ground ball, then turned towards 3rd base and threw the ball; I watched as the 3rd base player stepped on the base and outstretched their gloved hand to receive the throw; I watched the 3rd base player’s glove as the ball entered the pocket, and they brought their glove down to block the runner’s path to the base; I saw the runner attempt to avoid the tag by sliding in the dirt. It was close. The closest play I had to call all game, but not all season. I called the runner out.

The fielders were thrilled. The runner accepted their fate and stood up and walked back towards their team’s dugout behind the first base line. I heard the moans and groans from the runner’s team in the first base dugout, and that team’s parents behind it. And I heard the coaches. Boy did I hear the coaches. One coach came out of the dugout with his arms over his head yelling at me. “Anyone watching that play saw that she was safe. THERE WAS NO WAY YOU SAW HER OUT.” He clearly saw the play differently than I did (or he was lying about what he saw in the hopes it would change my mind, but does that really work on an umpire? Please tell me “no”.)

Based on his reaction, and the reactions of those around him, I believe he genuinely saw something completely different than I did. But what the coach and others saw is likely based on what they were looking for, and hoped to see. The coaches, players, and parents for the runner’s team were probably focused on the runner in the play. They saw their runner doing everything right. The coaches, players and parents for the runner’s team were probably not looking at the details of the fielders’ work. They were probably so focused on watching their player attempt the first slide of the game, that they didn’t see the third base player catch the ball and tag the runner before she made contact with 3rd base. They weren’t looking at it, or for it, and therefore didn’t see it, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Though short on experience umpiring, I am long on experience coaching. I was not going to argue with the coach. I knew I had looked at all the right parts of the play. I called what I saw. There was no way I was overturning my own call. So, I simply turned to him, looked him in the eye, smiled and said “ok”. I was not agreeing with him and I was not going to change my call, either. I then looked past the coach into the dugout as I called for their next batter. The game went on.

The runner’s team eventually won the game. It wasn’t even close. That call didn’t impact the outcome of the game. They were looking for the win, and they ultimately got what they were looking for, even if they didn’t get the call.