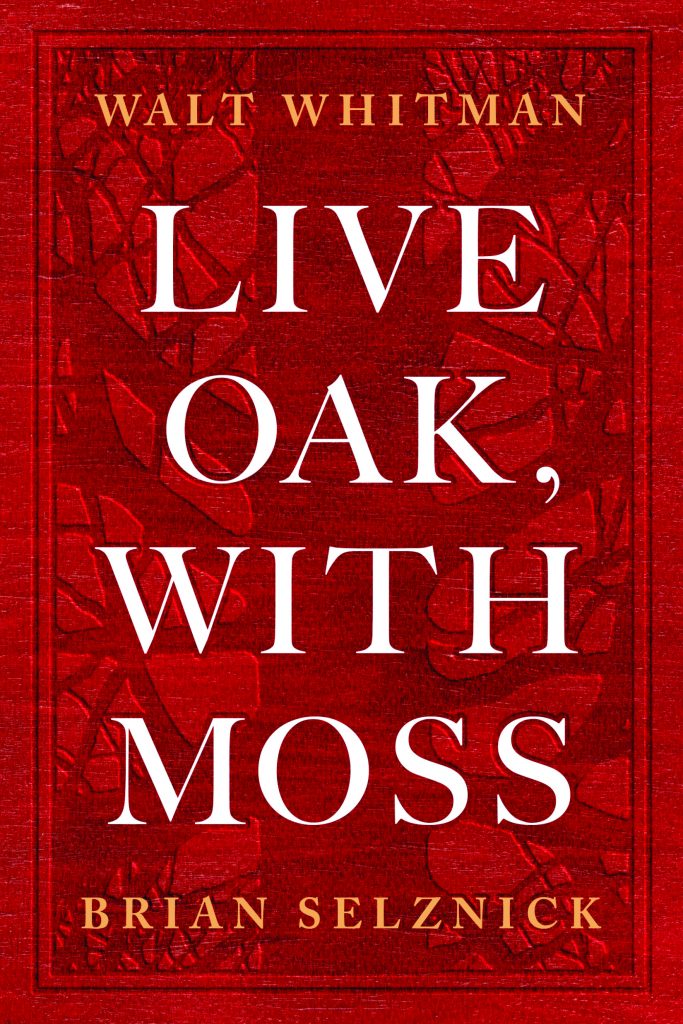

How the hidden, queer verse of Walt Whitman found a safe space amidst the illustrations of an adored children’s book author.

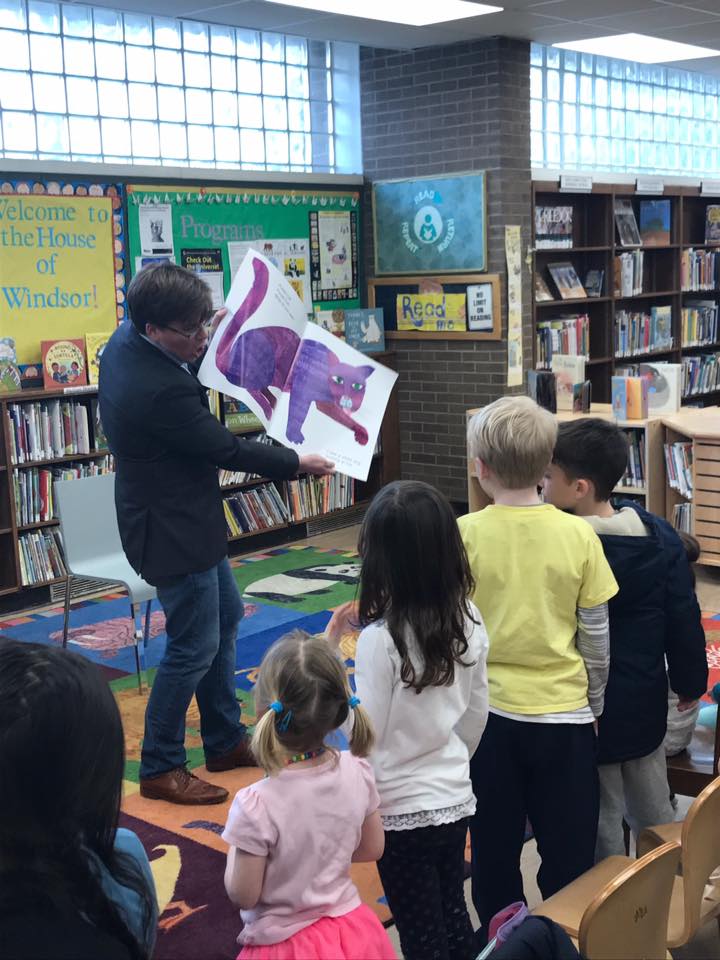

Walt Whitman hid a big secret in Leaves of Grass. Brian Selznick, author of The Invention of Hugo Cabret and Caldecott Award winner, has long been a collector of the book, but he never read a single line. That is, until his revered mentor and longtime friend, Maurice Sendak, let him in on the secret only known in select literary and scholarly circles. Hidden within the pages of this celebrated collection of American poetry was another collection of poems, Live Oak, With Moss.

Now, upon both the 200th anniversary of Whitman’s birth—and the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots—Live Oak, With Moss debuts to the public in a format as never seen before, complemented with a visual journey courtesy of Selznick and contextual analysis by Karen Karbiener.

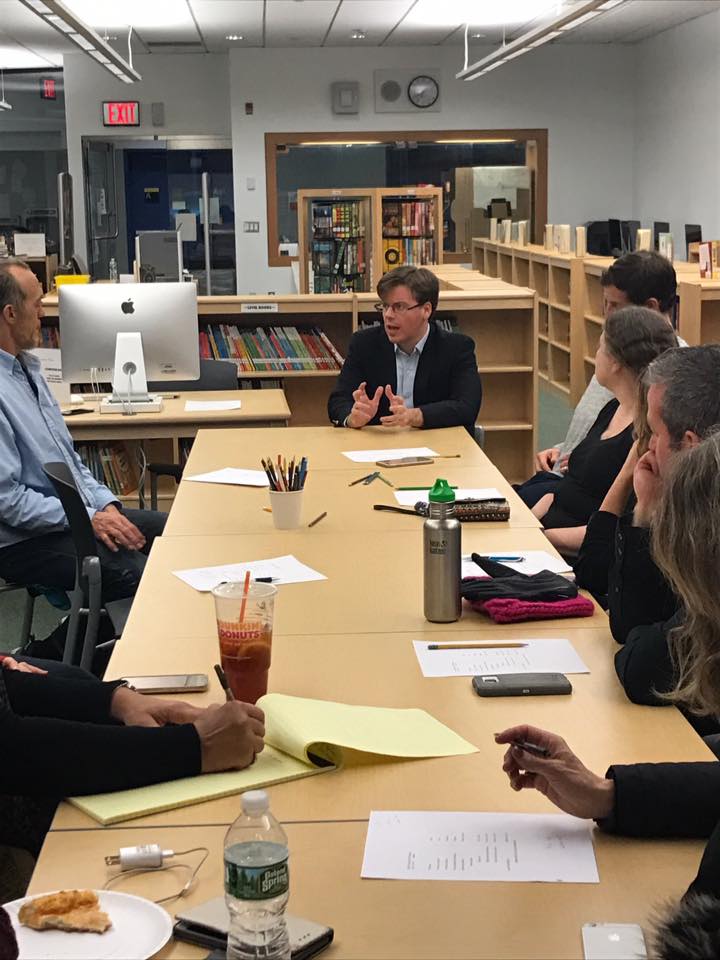

We sat down with Selznick in his Park Slope home to discuss the artistic endeavor of presenting Whitman’s Live Oak, With Moss, out, for the first time.

PARK SLOPE READER: In your forward to the book you acknowledge the major influence that Maurice Sendak had in your career and in inspiring this endeavor—including his stance that poems don’t need illustrations. How did this shape your approach to the book?

Brian Selznick: How do I justify the fact that I made this entire book? No, that was a really big issue for me because Maurice really had always been like a god to me. His work was the work that I had learned the most from.

There’s so much about our conversations that directly or indirectly led to everything I’ve done since we’ve met. I think one of the things that I had noticed even before this particular conversation was that he was really brilliant about what to illustrate and what not to illustrate.

If you remember Where the Wild Things Are you might remember that the only page that has no pictures is the last page where Max has come home from all of his adventures, he’s left the wild things and he ends up back in his room, and his mother, who had sent him to bed without any supper, has left his supper for him waiting. And you turn the page and it’s all white except for the words, “And it was still hot.” He could’ve drawn Max sitting happily eating the supper and his mom maybe looking through the crack of the door over him, but Maurice chose not to draw a picture on that page. . . . No matter what he does, his mother still loves him and that doesn’t need a picture.

My interpretation of what he meant was that poetry is designed as a communion between the poet and the reader, and that anything an illustrator does will interfere with that communion.

Because he said he didn’t illustrate stories. He tried to illuminate them.

This collection of poems has never really existed on its own in print. It’s now out and it’s visible and it’s consumable, and it did feel as though you were respecting that.

Brian Selznick: Well, that was definitely the intention and the fact that the poems themselves were hidden and then revealed is itself something that parallels what most queer people experience in terms of coming out.

[Whitman] never talks about these poems in any of his letters to anybody. There’s no indication in any of his other writing that anybody ever knew about this sequence. One of the things Karen Karbiener talks about is how special it is and how powerful it is that he wrote these poems about this part of himself that people didn’t even have language for.

In one of the poems he actually says the line, “I am what I am.” Karen identifies that as this moment where he comes out to himself for the first time, and that’s a very powerful thing to recognize and to see and to have written.

You’ve spent most of your career working on very obvious narrative arcs, and this, by contrast, must’ve presented a unique challenge. You’re dealing with something in the abstract. How do you approach that as an artist, and can you talk about the different process you took in producing this?

Brian Selznick: I’m a very narrative-based thinker and so all the books that I’ve done up until this are really built around the story. Even when I’m writing my own books, like The Invention of Hugo Cabret or Wonderstruck or The Marvels, I always start with the plot first, and then the second thing I figure out is characters, and then the third thing I figure out is motivation. So, it’s this weird, very backwards way of working. But, it’s somewhat mechanical in certain ways in that I need to know what’s happening in the plot in order to know who the characters would be that would make that plot happen.

Then, after working on something for a year or two, I figure out why the characters are doing the thing that makes the plot happen. And I think that’s partially why I’ve always really loved abstract art and always secretly wished that I was an abstract artist, because I’m so tied to plot.

I do see a narrative arc in Whitman’s poems and it was described to me by Maurice as a poem about a love affair that Whitman had with another man that ended, and then Whitman is dealing with the grief of the end of that relationship. (And Karen and most scholars now argue that it’s not necessarily about a single relationship; it’s larger and more esoteric than that.)

But still, when I think about the movement through these poems, I still see or create a narrative, but I think that’s very human thing to do. We make narratives out of everything, and I think that most of us even look at abstract art and often we’ll put a narrative on it.

He wrote these poems about this part of himself that people didn’t even have language for.

You are a children’s book illustrator, primarily, but Live Oak, With Moss is intended for adults. Was that at all freeing for you? Was it challenging? Did it matter at all?

Brian Selznick: It did matter. When I write my books for children I actually don’t think about children when I’m writing. I’m just trying to make a good story.

Which is why I think they’re so beloved by adults as well.

Brian Selznick: Oh, good. I’m aware that most of my audience will be kids, and the reason I think my work is for kids is because my main characters are kids. But that’s not really a choice I’m making. It’s just that the stories that come to me are about people who are between the ages of 10 and 12 years old. Because of that, I’m aware that people who are that age like to read about themselves, and the only concession I make to children when I’m thinking about my stories is that I know that I’m not going to use curse words, and I know that there’s not going to be sex scenes.

Other than that, there’s no concession to kids, which is why I often end up writing about things that either grownups don’t even know about or you find out in grad school—like the history of French cinema or the history of museums and the cabinets of wonder and memory palaces, which is part of what Wonderstruck was built on, or 19th century theater and the AIDS crisis which was at the heart of The Marvels. These are not general topics for readers who are 10 to 12 years old.

I was conscious of that fact that I was making something for grownups and wanted to be honest about what I was making—and honest about the queerness of it and the sensuality of it, but I definitely was aware that I didn’t want to do anything that, if a kid was to see, it would be too upsetting. There’s naked men in this book. There’s this sequence where we see the bodies touching, but there’s nothing identifiable in it that I think would be shocking to anybody.

Live Oak, With Mosshas a lot of literary and creative heritage imbued in it. Could you talk how you felt bringing all of this together?

Brian Selznick: Yeah, well, I mean nothing exists in a vacuum and everything that we create is something that comes out of what we’ve learned about what our experiences are, who we’ve encountered, what artists move us. In so many ways, anything you look at you can trace back through the history of time and probably find some precedent for any story that’s been written somewhere in the Bible or the Mahabharata or in Greek mythology.

The roots for all of these stories and all of us as artists, I think, is pretty easily traceable throughout all of time. Maurice, for me, has always been the central artist, and after I did a couple of picture book biographies—the Whitman book, one about Marian Anderson, one about Amelia Earhart and Eleanor Roosevelt, one about a dinosaur artist named Waterhouse Hawkins—and I ended up getting stuck after that. I didn’t know what to do, and that’s around the time I met Maurice and I just sort of clicked myself into Maurice Sendak university. Whatever he mentioned to me, whatever poem he mentioned, whatever novel he mentioned, whatever painting he mentioned, I would then go and look up, and read or dive into, or learn more about if I didn’t know about it.

That’s why I first read Moby Dick—because he loves Herman Melville so much and Emily Dickinson, and Van Gogh as I had mentioned earlier. He offered me a gateway in a lot of ways into all of these early 20th and 19th century artists who themselves were then coming out of so many other artists before them. I love what Karen talks about with Whitman looking at Shakespeare and purposefully taking things from him and trying to parallel and trying to say America can make someone like you, too. Like, I can be what you are in England in the world, but I can be expressly American, and America has the talent and the breadth to do that. This new country can create an American bard. I think that that very much is an inherent part of the creation of the book—it is all of these connections: The Victor Prevost black-and-white photographs of the city, and the idea of the city has portraiture and then some of the photographs are the naked men by Thomas Eakins and Edward Muybridge.

Eakins, who painted a lot of naked young men, also very famously photographed Whitman at the end of his life and knew him. I think maybe I knew that a little bit, but that connection became stronger once I was putting the book together, realizing that I was using photographs by someone who had later photographed Whitman.

The fact that so many of these images are by Edward Muybridge, who people credit with the beginning of cinema. . . .it makes sense that the book itself is a web of all of these artistic connections. If you go to Shakespeare, if you look at all of the writers who he was inspired by, he hardly made up any of his plots! He would read this myth and then this story, and then that play and the write his version of it. But, of course, his version of it was a billion times better than any of the previous ones, and it becomes the one that we know. And it becomes . . . he imbues it with his genius.

As long as there are artists making art, Maurice’s work will be there as an inspiration and as something beautiful the way that all the people he loved will continue to inspire people.

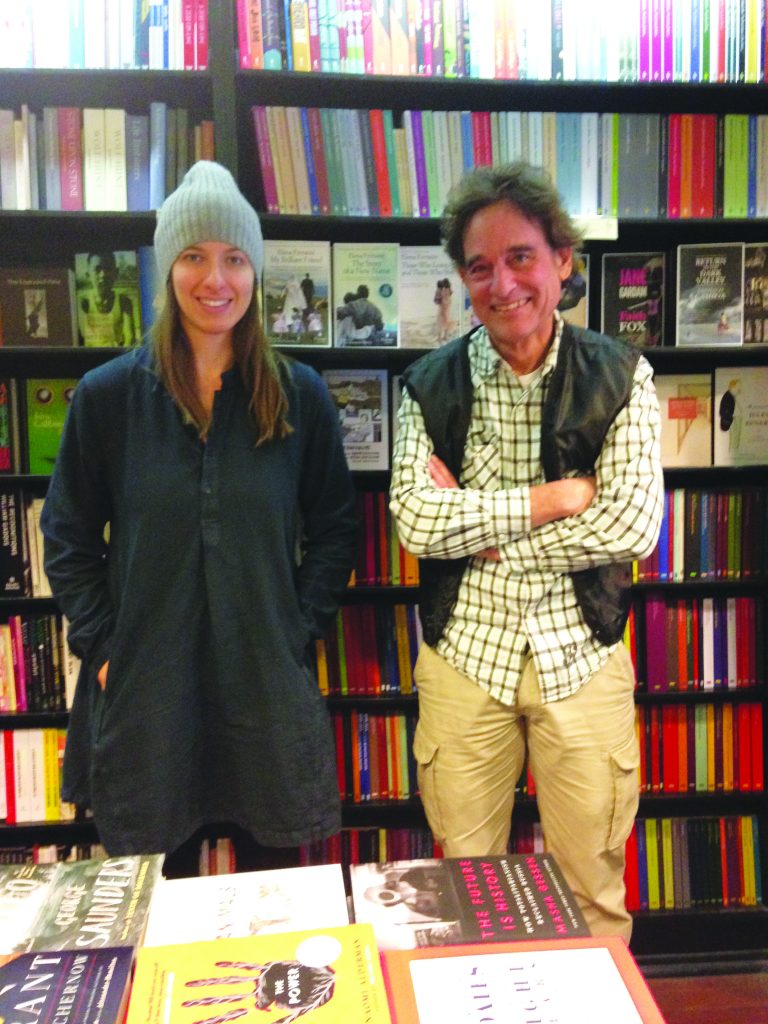

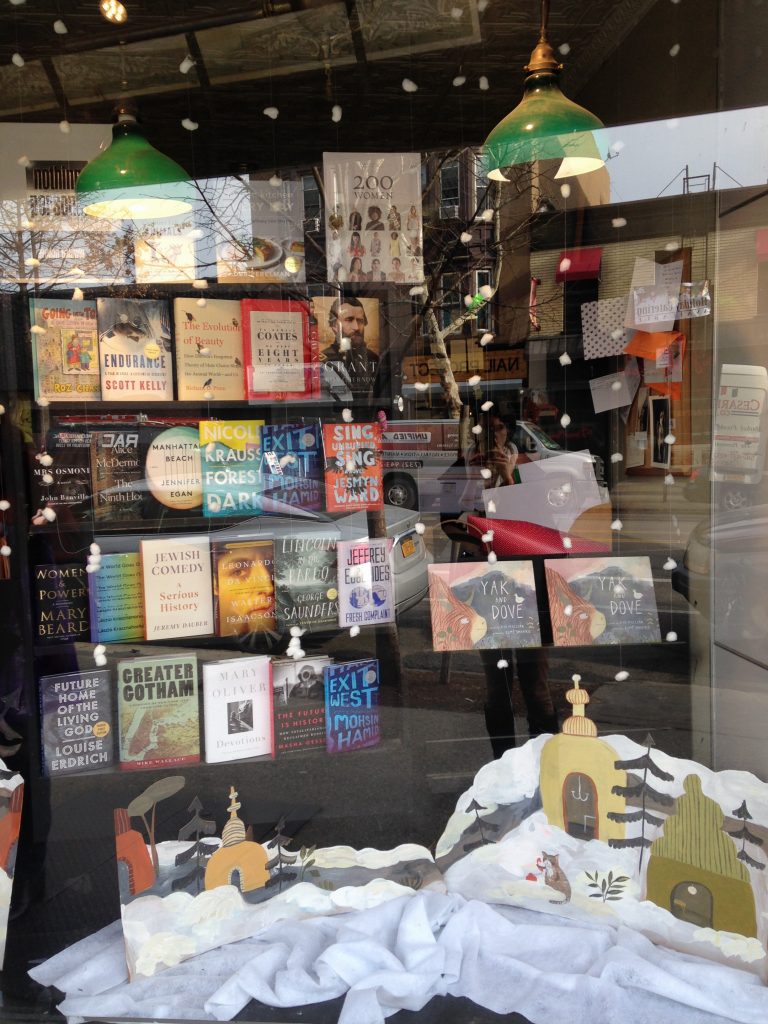

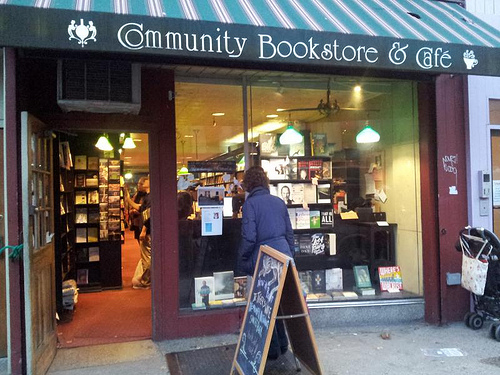

“You’re really catching us on quite a day,” said Stephanie Valdez when I met up with her and Community Bookstore co-owner Ezra Goldstein one afternoon early in December. Not only was the usual holiday rush upon them, there were last-minute children’s book fairs to coordinate (“it’s almost like setting up two more stores”), book orders to be completed without delay, and sniffles to be suppressed as best one could. (All sneezes have been omitted from the following conversation.) Yet the staff was in good cheer. When I arrived, Ezra was standing by the front register regaling several employees and a customer with a story. Stephanie laughed as she typed busily at the computer, while store mascot Tiny the Cat lounged with characteristic disinterest inside his basket in a corner of the window.

“You’re really catching us on quite a day,” said Stephanie Valdez when I met up with her and Community Bookstore co-owner Ezra Goldstein one afternoon early in December. Not only was the usual holiday rush upon them, there were last-minute children’s book fairs to coordinate (“it’s almost like setting up two more stores”), book orders to be completed without delay, and sniffles to be suppressed as best one could. (All sneezes have been omitted from the following conversation.) Yet the staff was in good cheer. When I arrived, Ezra was standing by the front register regaling several employees and a customer with a story. Stephanie laughed as she typed busily at the computer, while store mascot Tiny the Cat lounged with characteristic disinterest inside his basket in a corner of the window.

The characters in Forest Dark are neither “empathetic people from the first page,” as they were in The History of Love, nor are they quite those “who, from the first, were difficult people, as people are,” such as populated her Great House. They defy easy categorization while tempting you to draw connections between their own journeys through parts unknown with what you might think you know of Krauss. They include the elderly Jules Epstein, a wealthy and formerly gregarious New York attorney who has begun selling off his considerable possessions. On page one we learn he has disappeared from the rundown Tel Aviv apartment in which he had been living alone. And we have the protagonist of a parallel story that, in true Krauss fashion, is recounted in alternating chapters, a novelist living in Brooklyn with two sons, and a husband from whom she feels increasingly distanced. Ostensibly to research a new book, she, too, leaves for Tel Aviv. Her name is Nicole.

The characters in Forest Dark are neither “empathetic people from the first page,” as they were in The History of Love, nor are they quite those “who, from the first, were difficult people, as people are,” such as populated her Great House. They defy easy categorization while tempting you to draw connections between their own journeys through parts unknown with what you might think you know of Krauss. They include the elderly Jules Epstein, a wealthy and formerly gregarious New York attorney who has begun selling off his considerable possessions. On page one we learn he has disappeared from the rundown Tel Aviv apartment in which he had been living alone. And we have the protagonist of a parallel story that, in true Krauss fashion, is recounted in alternating chapters, a novelist living in Brooklyn with two sons, and a husband from whom she feels increasingly distanced. Ostensibly to research a new book, she, too, leaves for Tel Aviv. Her name is Nicole.

Can you walk us through the process of selecting the lineup for the summer? How is this summer different from other years?

Can you walk us through the process of selecting the lineup for the summer? How is this summer different from other years?