An invincible nostalgia for an unlived experience is illuminated through Meejin’s art.

Anna Meejin’s paintings of landscapes, dinner plates, portraits, and horses cover the walls of her Brooklyn home. The large-scale paintings are hung salon-style against exposed brick, juxtaposed with ordinary household furnishings and decor. The lushly smooth surfaces with rich color palettes and ambient metaphor reveal a totality of nuanced domesticity, cultural patrimony, and the complexities of American history and Western civilization. Meejin’s paintings pay homage to the people and events in her life while reflecting a perpetual curiosity about a culture she has never known.

Meejin’s legal name is Anna Mee-Jin Hurley-Echevarria. She was born in Manhattan and raised between New York City and Puerto Rico. Anna’s mother is Puerto-Rican; her father is of Irish heritage. Although she was raised in a culturally pluralistic home in one of the most diverse cities in the world, Meejin always knew she was adopted. The striking physical differences between her and her parents were inevitable. The enforced societal expectations of constructing an American identity—for a child growing up in the early 2000s among rapid technological advances and economic crisis— led Meejin down a tumultuous road of self-discovery in an extraordinary period of US history.

“I was always trying to figure out where I fit in,” Meejin told me over the phone. “I knew I was Korean but never had a relationship with my culture.”

In the series, Considering Her Past (2020-21), Meejin explores the delineation she often feels from her Korean identity, while simultaneously searching for her place in contemporary American society. Painting through the pathos of confusion and detachment, she creates exaggerated portraits of Korean women and fictional horses. Traditional objects of cultural importance entangle with narratives told but not lived. The illustrative compositions examine the dichotomy between what is and what could have been.

“I was going back in time learning about the traditional things,” Meejin explained. “I was thinking about an experience I never had.”

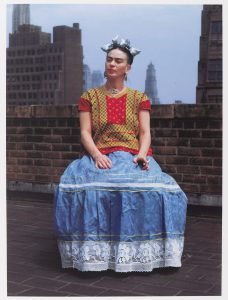

In “Sweet Thoughts” (2020), an invincible nostalgia for an unlived experience is illuminated through the portrayal of a seated Korean woman, holding an intricately crafted folding fan. The traditional Korean fan, called a hapjukseon, dates back to the Goryeo Dynasty which ruled Korea from 918-1392. Covering the slim bamboo strips and the delicate frame is a painted landscape, applied directly to the hanji— a fine handmade paper made from mulberry trees. The hapjukseon covers the nude female figure, whose stylized anatomy and downward gaze are placed in the center of the composition— and are confined by the barriers of the canvas. Her porcelain-white skin and rose-colored makeup date back to the cultural aesthetic of early Korean Dynasties, long before Eurocentric beauty standards came into existence. The figure is ungrounded, floating in a dream-like state through lulling brushstrokes that sweep across the surface of the canvas.

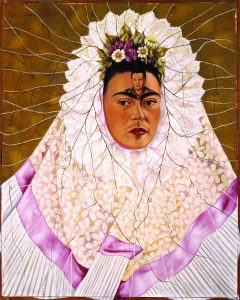

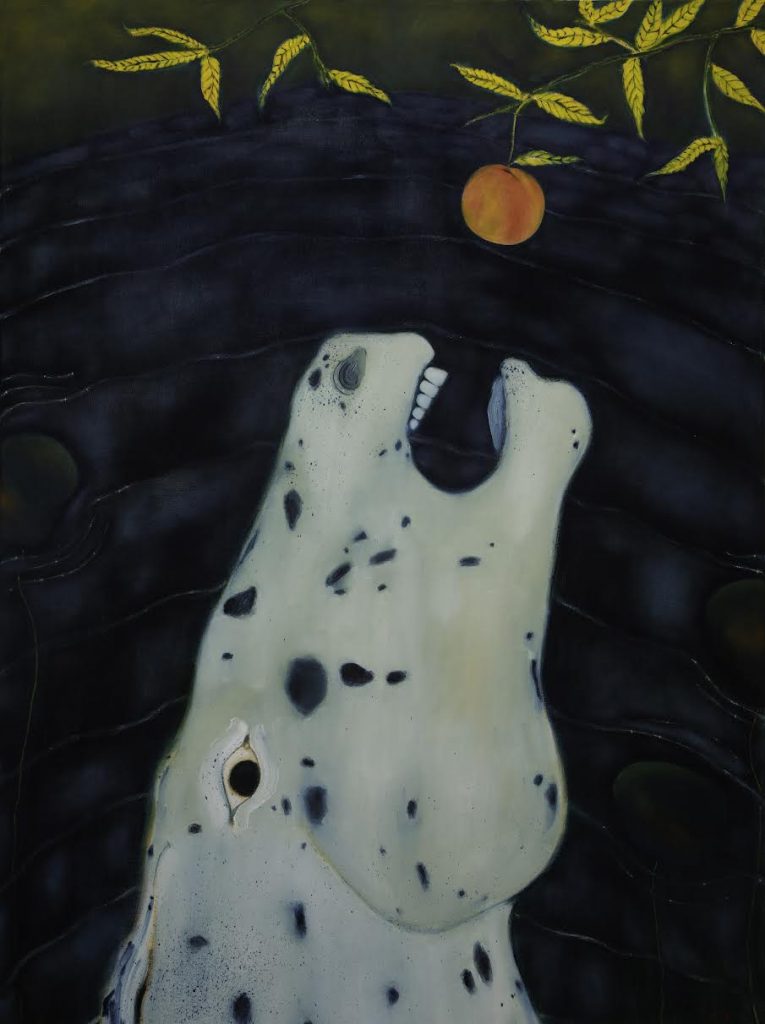

In “The Last Peach” (2021), Meejin creates a fictitious world to poignantly route her lived experiences. The painting is paramount to Meejin’s Korean-American identity; the narrative is heavily influenced by Western allegory and Korean metaphor. A celebrated horse, symbolic of the historic European ideals of power and conquering a people or place, is painted in the center of the composition. The horse’s neck is outstretched; his jaw is defined. His gaze is determined by greed. Dangling above the horse from a flimsy tree branch is a ripened peach. The peach is vibrant, fresh, and representative of Korean ideals of abundance, fertility, and longevity. It is a symbol of wealth that taunts the horse, whose form becomes distorted with the desire to obtain its fortune. In the backdrop of the painting is a pool of water that eventually drowns the horse.

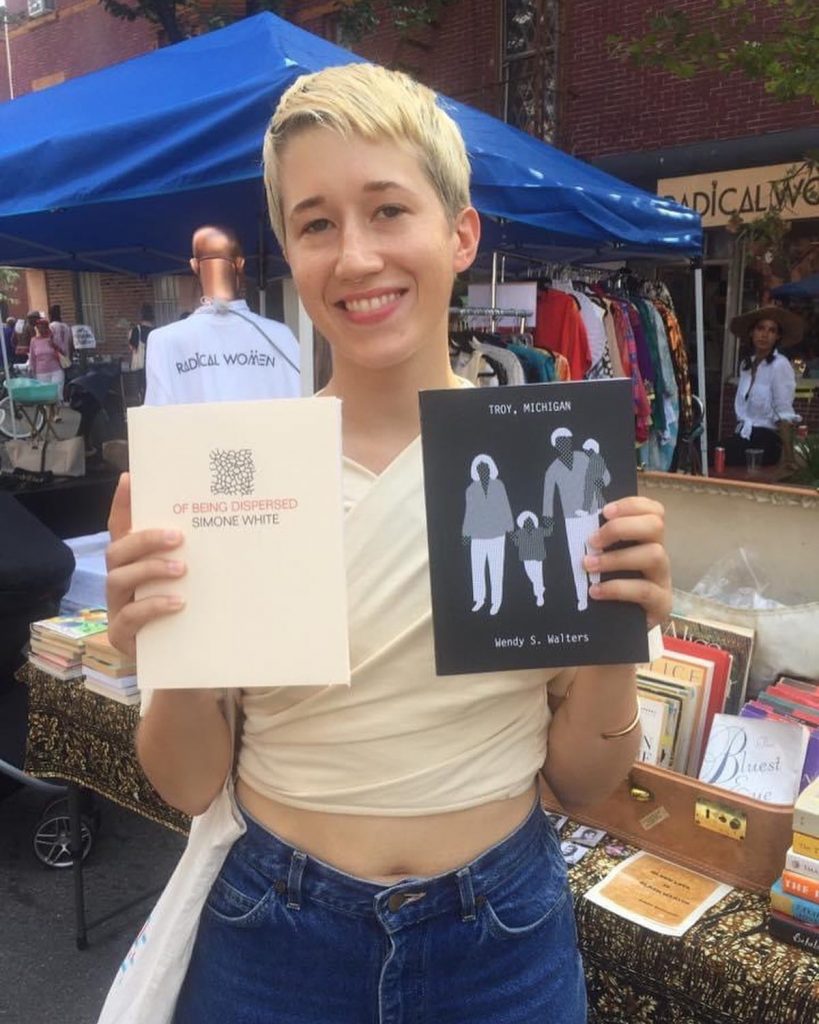

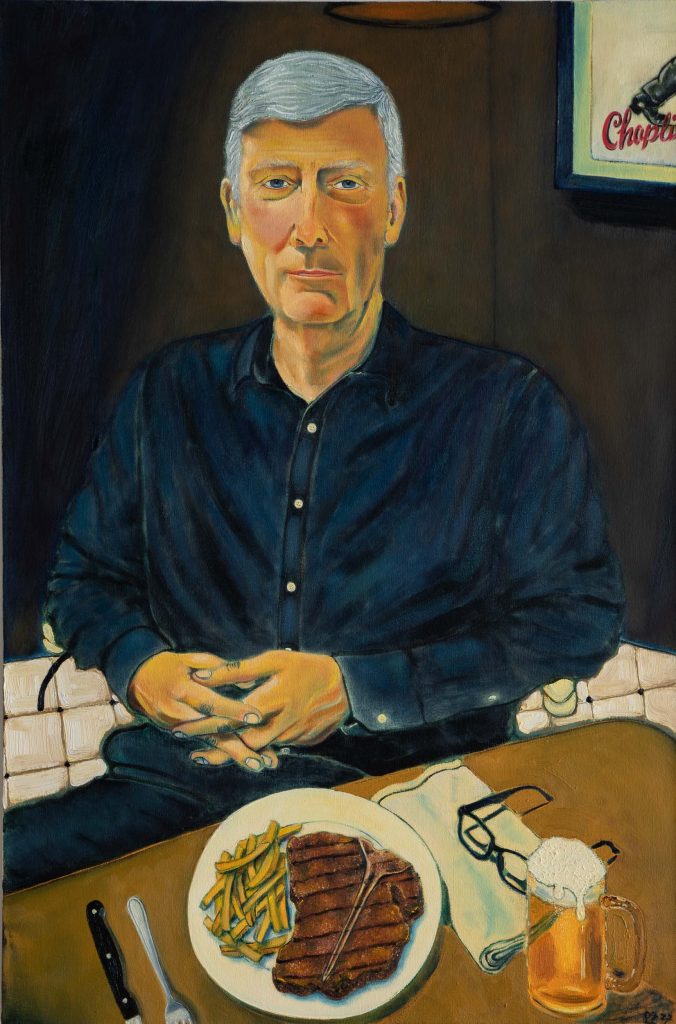

In her recent work, Meejin has turned to those around her for inspiration. Oil paintings of friends and family members have shifted Meejin’s aesthetic from personal narratives to the subtleties that encompass the existence of others. Nuanced scenes of domestic routine warrant the stoic expressions of the figures who gaze back indifferently at the viewer. The figures sit in chairs at dinner tables and desks. They eat dinners of steak frites and snacks of delicately sliced fruits. They read books and smoke cigarettes. Bold color palettes and atmospheric lighting set the tone of the paintings— elongating the forms and evoking a sense of belonging. The paintings provide an astonishing direct line to reality and the shared human experiences that exist in all cultures.