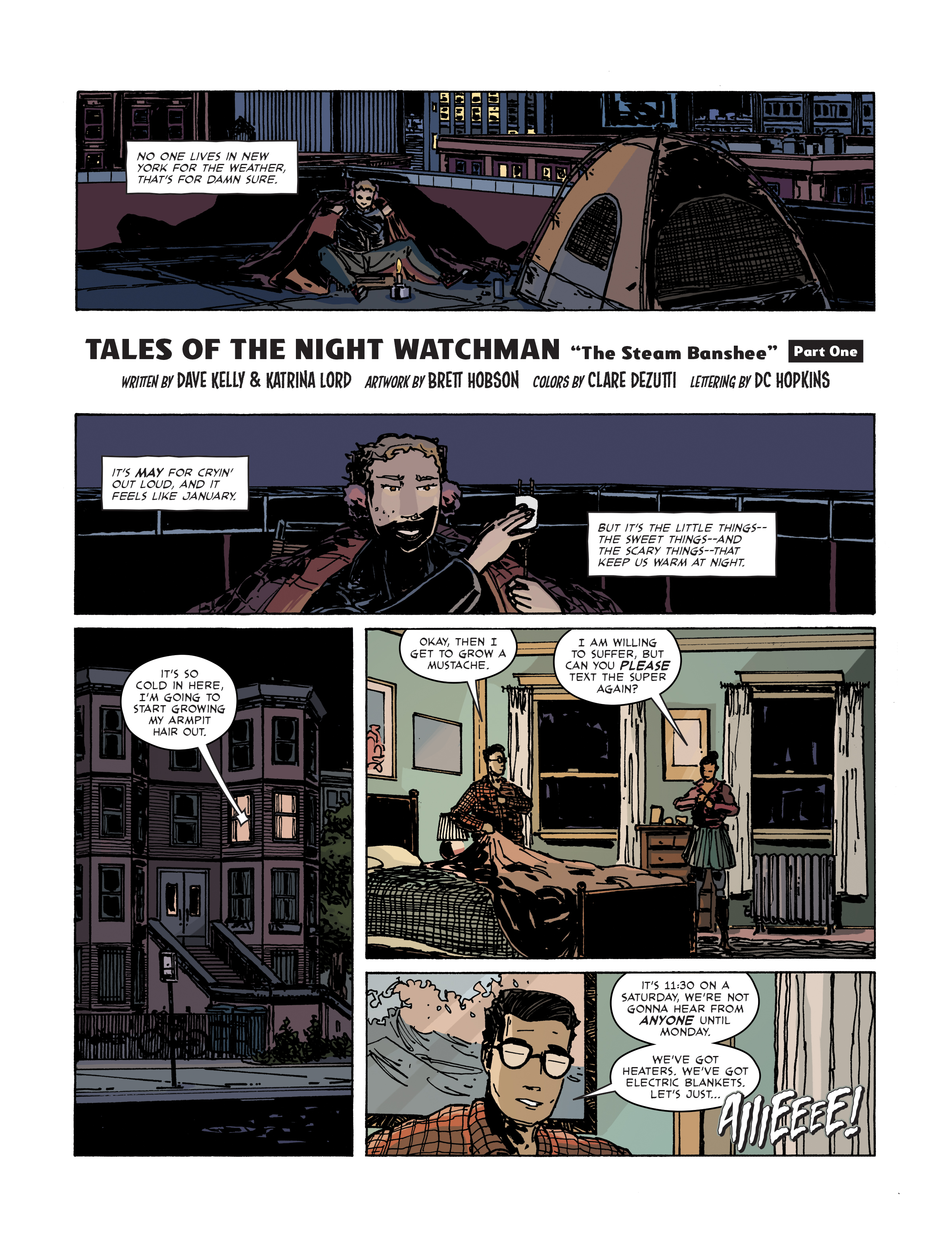

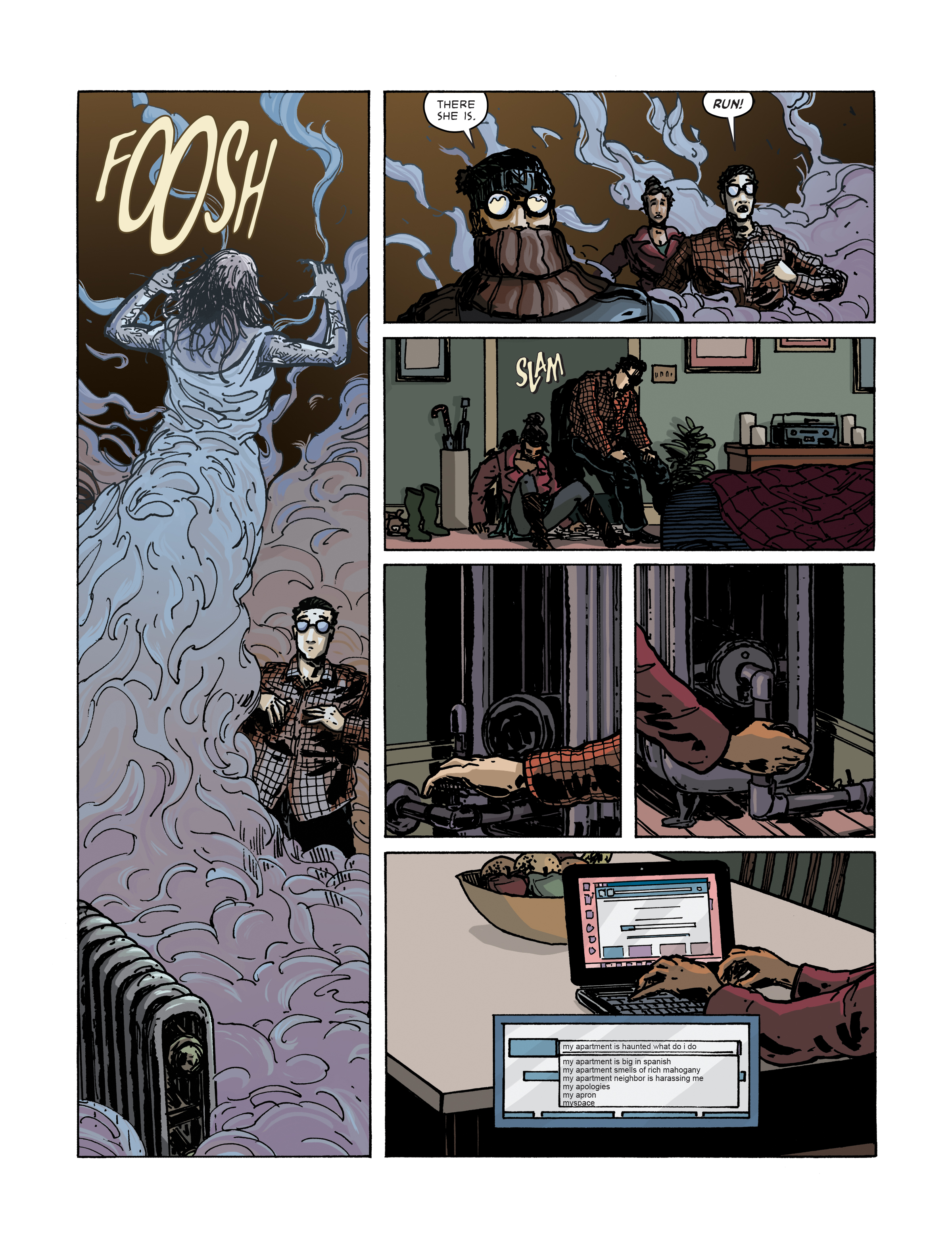

Tales of the Night Watchman is the story of three baristas and a city full of monsters. In The Steam Banshee Pt. 1, a Park Slope couple finds their quirky neighbor upstairs isn’t exactly living alone.

By Dave Kelly, Katrina Lord, Brett Hobson, Clare DeZutti, & DC Hopkins