Known for housing extraordinary exhibitions of art and media, The Brooklyn Museum has always brought history and contemporary culture together in unique perspectives. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving (running from February 8th to May 12th, 2018) is no different.

If you are expecting to see rows of Frida Kahlo’s beautiful, colorfully painted self-portraits you will not find them here. Instead, for the first time in the United States, the exhibition displays the iconic artist’s trove of personal photographs, clothing, and belongings.

After her death in 1954, these possessions were locked away under the instruction of her husband, muralist Diego Rivera. Fifty years later, uncovered from her life long home, Casa Azul, The Blue House in Mexico City, they now lay on display to explore Frida’s work in relation to that which surrounded her. This framing is what makes the exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum so unique. With only twelve of her paintings within the 350 objects, the exhibition itself questions what is more important- the art or the artist?

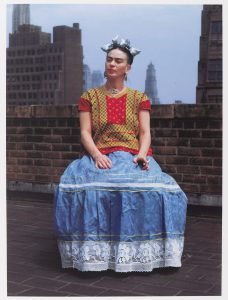

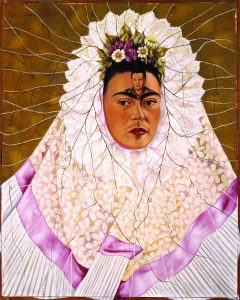

Frida painted her image in the same manner that she presented herself every day. In both appearance and art, she dressed in the fashion of the indigenous Tehuantepec women of Southern Mexico; with her long enagua skirts, huipil square cut tunic, and braided hair decorated with blooming flowers. She challenged the growing Euro-centric beauty standards by noticeably darkening her skin in paintings and highlightings her thick facial hair and eyebrows; while also celebrating her femininity, wearing traditional lace resplandor garments. The ruffled white lace framing her done-up face like a flower. These hand-made dresses are featured in personal photographs and on petite mannequins complete with floral headdresses and heavy pendant jewelry. No two dresses similar in detailed design.

Her appearance cemented her identity with Mexico motivated by her personal, political, and artistic convictions. Raised by a mother of Indigenous and Spanish descent and German immigrant father against the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution, Frida became educated in her Mexican heritage both colonial and modernist. She contracted Polio at a young age and later suffered a broken spine and injuries in a severe trolly accident. She began painting, fixated on her own image in the mirror as she lay hospitalized for months. These injuries would stay with her, causing her several miscarriages and need for abortions. She joined the Mexican Communist Party in 1928, immersing herself in political and intellectual issues alongside her husband, Diego Rivera. She also took a leading role in the Mexican Muralist Movement.

Seen in the love letter from photographer Nickolas Murray- with whom she had an on and off affair- he, maybe ironically, applauds Frida for her devotion. Frida Kahlo had a strong devotion to herself- her identity, her beliefs, and above all her art as she painted her way through pain, love, heartache, and joy. Never giving up or compromising on her own image, Frida meticulously crafted a visualization of her identity.

From the small Aztec sculptures to her painted diary entries, this personal story is told with each piece in the collection. Showcased at the center of the exhibition is the pink lace garment and flower headpiece she dons in the self-portrait Diego on My Mind (1943). The huipil grande headdress, a defining accessory of Tehuantepec women, was found on a statue of the Virgin Mary, attracting visitors to gather round. Contrastingly, the actual painting featuring the garment, complete with gold leaf and Diego’s figure above Frida’s striking brow, is tucked in the corner of the room.

Under the square tunic blouses, Frida wore an orthopedic, leather-bound corset that assisted in supporting her fragile spine and back. Pages of medical reports and documents give information on her clinical history are uncovered. Her prosthetic leg with traditional Chinese fashion inspired laced up boots, which she strategically hid from prying audiences under her large skirt, come to light. Also displayed are Frida’s plaster cast corsets covered in some of her first paintings composed as she lay after surgery with a mirror about her body. On one she paints a fetus over her abdomen, another a gaping empty space on the stomach. One other features her spine as a broken column cracking and crumbling to dust. On two she paints a large, red Communist hammer and sickle over her heart. Frida, herself, chose to keep these casts once they were taken off, perhaps as a way to remember and document the suffering she endured which worked to fuel her creative energy. A surrealist drawing from her diary shows her as a one-legged child, inscribed “Feet, What Do I Need Them for If I Have Wings to Fly?”

So with her art, and furthermore her everyday life, is Frida daring us to be bold and live to outwardly express ourselves?

Frida’s image was conscious, considerate, complex, and strategic. In photographs, she posed in such a way to hide her disability, but even that which was private and purposefully covered up was essential to her identity. Contrastingly from these private elements, greenstone and jade beads, finely carved rings, silver earrings, and heavy gold Tehuana necklaces materialize under glass cases. Some would say this heavy jewelry and flower crowns would upstage the young artist’s petite figure, but others saw the significance of the overpowering look. Each beautifully crafted works of art in themselves, which Frida was adamant to decorate herself with. Personal photographs document her enjoying Mexico City’s markets and the purchases she made there- rings, dolls, and decorative trinkets. Frida was known never to barter for goods, indicating a belief in the value of material things.

She cultivated these purchases in a collection of gems, clothing, writing, sculptures, and even animals at The Blue House. Often housebound due to her disabilities, Frida created a microcosm of Mexico within her own home. Filled with craftsmanship that celebrated Mexican history and culture, every element that influenced her life came together in The Blue House. There she cared for monkeys and other animals as pets- or perhaps as surrogate children-, decorated with Olmec figures as her alter egos, and hung mirrors around every corner to compose her appearance throughout the day. Appearances Can Be Deceiving gives us a glimpse into the highly detailed world Frida cultivated- a treasure trove of her integrated parts of her life, art, and identity.

Just as the objects around her were important, so were the people. Frida surrounded herself with like-minded artists and individuals that helped to record her artistic legacy. The influence from her parents, her sister- who had an affair with her husband-, American photographers Lous Pachard and Imagen Cunningham, and of course her husband, Diego Rivera. About him, the subject of many of her paintings, Frida writes, “I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down… The other is Diego.” Referred to by their family as “an elephant and a dove,” the exhibition has hundreds of photos and films of the couple painting, at political events, traveling, and living in The Blue House together. In the press, Frida was often referred to in relation to her husband. It is interesting enough to wonder if Frida knew that in the future her name would largely mean more to us than his. But maybe she did as she stated seemingly realizing her own importance and iconic image, “All the painters want me to pose for them.”

Photographer Imagen Cunningham said that people marveled over Frida’s appearance when she came to the United States. And how is that any different from today? As I walked through the museum, I came across a young woman dressed as Frida Kahlo, in full hair, makeup, and costume. Still today the bright, beautifully woven colors and patterns of the Tehuantepec style highly contrast the black, solid prints of modern New York fashion. Ironically enough, the one black colored dress in the exhibition, Frida wore to a New York art show and dinner event in 1933. From her fiery red lipstick to her embroidered skirts, to her shoes from New York or San Fransisco’s Chinatown to her iconic unibrow, Frida’s appearance was truly her own.

No piece of her was without thought. In mind, body, and appearance, Frida was aware that every part of her being brought about her values and message. Whether she cared if we agreed or not, Frida worked for others to know who she was through her open visual identity. Proving this, on the back of her mother’s First Holy Communion photo Frida writes in pen “Idiota!”. She has even stated, “I do not like to be considered religious. I like people to know I am not.”

So with her art, and furthermore her everyday life, is Frida daring us to be bold and live to outwardly express ourselves? Or did she simply not care about us- the audience- using her self portraits and painting as just another way to curate her uncompromising identity? If so, what does this exhibition signify- where do the importance and meaning lie in these personal belongings? The title of this exhibition, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, suggests that there is more to what is outwardly presented. So if Frida was in fact so adamant about visually presenting and cultivating her identity, what deeper truths are there to be uncovered? I urge you to visit this must-see exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum with these questions in mind as you walk through surrounded by the same items and objects that Frida Kahlo chose to surround herself with.