Image courtesy of the Office of Governor Andrew Cuomo.

To most, public art may seem innocuous. Art brings vitality to public spaces. It helps districts establish identities, provides artists with income, and boosts local economies by providing sought-after destinations for art lovers. And perhaps more importantly, public art provides an opportune backdrop for tourists and selfie enthusiasts. However, for New Yorkers who are especially inundated with public artworks ranging from historical tablets and monuments in public parks to contemporary works, like Jeff Koon’s colossal Balloon Flower and Jenny Holzer’s impermanent text-based projections, the relationship between the public and art is not always positive.

Public art is rarely considered by art critics to be “good” art. Seldom does it arrive without a myriad of complications. Aside from often being overly symbolic or kitsch, public art is largely taxpayer-funded, governed by private capital, and decided on by a panel of bureaucrats.

In 2020, the city planned, commissioned, and installed dozens of public sculptures, installations, murals, and artworks. Below are three of the most recent public sculptures to be unveiled, all of which were met with varying degrees of controversy.

Mother Cabrini Memorial

Giancarlo Biagi & Jill Burkee-Biagi (2020)

A bronze and granite memorial honoring the life and service of St. Francis Xavier Cabrini, the Patron Saint of Immigrants, was recently erected in Manhattan’s Battery Park City. Cabrini, more commonly referred to as Mother Cabrini, an Italian immigrant and devoted public servant, founded over 60 schools, orphanages, and hospitals, including numerous academic and health care institutions in New York City. She was the first naturalized American to be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, nearly three decades after her death. Although Cabrini’s legacy parallels the valor and perseverance of many immigrant communities, the memorial was heavily disputed by the public and follows a contentious stint of bureaucratic conflict between New York’s city and state governments.

“We are all immigrants in one way or another. We all share the immigrant experience,” said Italian-American artist, Giancarlo Biagi in an interview.

Biagi and collaborator, Jill Burkee-Biagi, were selected by the Governor Cuomo-appointed commission to complete the Cabrini memorial—budgeted at $750,000— in a remarkable nine months. The life-size bronze monument atop a marble base depicts a young Cabrini and two small children in a paper boat, gazing ahead into a distant future. It stands erect in a cove along the esplanade and against a backdrop of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty. The commemorative memorial is filled with metaphor, perpetuating collective immigrant experiences of hope and new horizons, while also containing small anecdotes of Cabrini’s mortality. The plaza is surrounded by mosaic, created from bits of riverbed stone near Cabrini’s birthplace in Sant’Angelo Lodigiano. The memorial was unveiled on Columbus Day and dedicated by the New York Governor.

The controversy of the Cabrini memorial—as with most memorials—lies within the boundaries of taxpayer-funded public art, the site-specificity of the artwork, and how the overall content and design are determined. In 2018, First Lady Chirlane McCray, Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, and the Department of Cultural Affairs announced the She Built NYC initiative, a project focused on funding public monuments and artworks to honor women’s history. The initiative builds on the recommendations of the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers— a commission that advises the NYC Mayor on issues surrounding public artworks and markers on City-owned property. An advisory panel, appointed by the de Blasio Administration, was founded to oversee the commission of large-scale commemorative statues of revolutionary women— including women of color, trans women, and non-binary individuals— to address the disparate gender imbalances in public spaces. The Department of Cultural Affairs committed to a budget of up to $10 million over the next four years.

The She Built NYC initiative, spearheaded by McCray, accepted public nominations via an online survey, receiving close to 2,000 responses in total. Although the submissions overwhelmingly favored a memorial honoring the legacy of Mother Cabrini, the panel disregarded the majority, sparking outrage among Italian-American and Catholic communities. In response to the outcry, the governor announced his administration’s plans to work with local Italian-American groups and the Diocese of Brooklyn to oversee the creation of a state-funded memorial to Cabrini.

The pandemic has indefinitely shelved the She Built NYC project.

Italian-American and Catholic communities applauded the decision to erect the Cabrini monument, however residents of the southernmost district of Manhattan disapproved— arguing that Cabrini had little involvement with the region. The Mother Cabrini Memorial Commission was able to bypass political disputes and reject public concerns for building the monument in Battery Park City— an area that is owned and controlled by a state corporation. In the long-term, taxpayers and residents of Battery Park City will continue to pay upkeep on an ever-increasing collection of public artworks, jointly valued at $63 million.

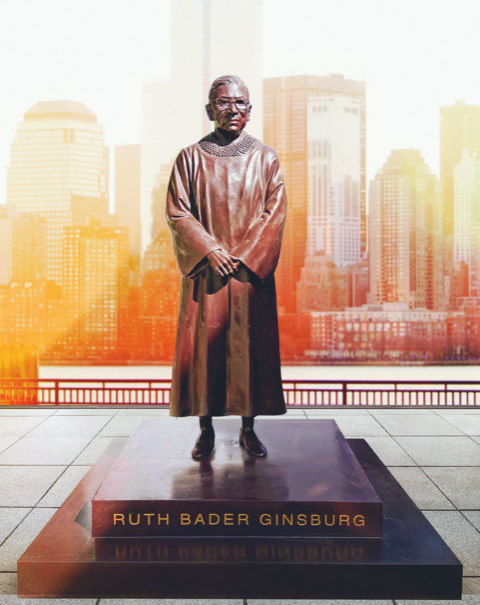

Ruth Bader Ginsburg Memorial

Gillie & Marc (forthcoming)

The nation is still mourning the untimely death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The announcement of her death, less than two months before the divisive 2020 election, was met with an outpouring of public grief for the beloved civil rights attorney and gender equality advocate. On the steps of the Supreme Court building in DC, mourners left makeshift memorials with handwritten notes, flower bouquets, and votive candles; public gatherings and candle-lit vigils were held in cities all over the country. The following day, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced in a tweet that the state plans to honor the life and legacy of Justice Ginsburg by erecting a permanent statue in her native Brooklyn.

Less than a month later, the governor appointed a 23-member commission to oversee the design and location of the memorial, including members of Ginsburg’s family. NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio also announced plans to rename the Brooklyn Municipal Building in honor of the late Justice.

Officials at City Point, a residential and commercial development in Brooklyn’s metropolitan center, said that the monument will be unveiled on March 15, 2021, coinciding with both Women’s History Month and Justice Ginsburg’s 88th birthday. The bronze statue, created by artist duo Gillie and Marc, was originally built in partnership with Statues for Equality, whose initiative aims to balance the gender, racial, and ethnic disparities of public sculpture. The artists believe that installing statues of women in public spaces are major steps forward in the long-overdue fight for gender representation.

Unlike the Mother Cabrini memorial, New Yorkers have mostly welcomed the forthcoming and permanent iconic statue of Justice Ginsburg. There has been little, if any, protest from the public regarding the budget of the memorial or upkeep. However, some in the art world wonder if the traditional solution of building a larger-than-life statue atop a pedestal is the best approach to memorializing the legacy of the adored American figure. Jerry Saltz, Senior Art Critic for New York Magazine, attributes “bad” and “generic” public sculpture to the bureaucratic systems that have long dictated public art— including the commissions composed of politicians, life-long political advisors, architects, and real-estate developers.

“One way to avoid this,” Saltz said, “is to, first of all, get a group of women together. I think you do not want the governor and another batch of male-whatever-politicians big-fucking-footing this thing around. [They should] just shut up and listen. Because to me, the monument to Ginsburg is not only a monument to Ginsburg; it is a monument to one of the greatest liberation movements in this country, which of course is feminism.”

Medusa with the Head of Perseus

Luciano Garbati (2008-2020)

One of the most controversial public sculptures of recent memory is Luciano Garbati’s, Medusa with the Head of Perseus. The seven-foot bronze sculpture of an unclothed Medusa reimagines the Greek myth by shifting the narrative of the myth to the perspective of Medusa while positioning the physical sculpture in the context of the #MeToo movement. Smooth and cold to the touch, but resolute and distinguished, Medusa gazes out above a sea of passersby. She is installed in Manhattan’s Collective Park Pond, across from the New York County Criminal Court where the Harvey Weinstein trials commenced.

The sculpture is inspired by Benvenuto Cellini’s 16th-century bronze masterpiece, Perseus with the Head of Medusa. As Greek Mythology recounts, Medusa was once a beautiful maiden whose appearance was transformed after she was stalked and raped by the sea god, Poseidon in Athena’s temple. As punishment for “breaking” the vow of celibacy, Athena turned Medusa’s hair into a tangle of snakes and cursed her with a gaze powerful enough to petrify men. Perseus, son of Zeus and Danäe, murders Medusa in her sleep. He holds her severed head in an upright, trophy-like position— weaponizing it to turn his enemies to stone. Cellini’s statue and Greek Mythology shame Medusa for being a victim of rape. The Argentine- Italian sculptor’s interpretation, Medusa with the Head of Perseus, flips the context, giving the power back to Medusa and victims of sexual assault.

At the mid-October unveiling, Garbati spoke of the women who had written to him, viewing the sculpture as catharsis. The artwork, created in 2008, has materialized into an artist-led project first conceived by Bek Andersen, called MWTH (Medusa With The Head – pronounced “myth”). Andersen contacted Garbati after the image went viral. Together, the two applied to NYC Parks’ program, Art in the Parks.

MWTH engages the narrative habits of classical imaginaries of the past, present, and future, and sells miniature replicas and agitprop of Garbati’s, Medusa. A small portion of the proceeds goes to the National Women’s Law Center.

Although the sculpture reimagines the myth by shifting the power to women—an act that is seemingly well-intentioned and fits into the narrative of feminist ideals— the artwork has been met with a deluge of controversy. For one, the sculpture predates the birth of the #MeToo movement by nearly a decade. Secondly, #MeToo was created by Tarana J. Burke, a Black activist from the Bronx. In a post, Burke wrote: “This monument may mean something to some folks, but it is NOT representative of the work that we do or anything we stand for.” In Garbati’s vision of Medusa, the Gorgon unrelentingly grips the severed head of Perseus and not the head of Poseidon, her rapist. This may be an act of irrefutable violence but artistically, it is not a radical political act. [Violence in art is nothing new.] The emphasis on violence and revenge in Garbati’s narrative conflicts with the entirety of the #MeToo movement. “This isn’t the kind of symbolism that this Movement needs,” wrote Burke.

The decision to erect Garbati’s Medusa is a classic example of a missed opportunity for minority representation that the City [and the art world] will continue to perpetuate. Instead, the City chose an artwork with a message created by a man, depicting a naked woman with an idealized muscular physique, Euro-centric features, and shaved genitalia.

A redeeming quality of Medusa with the Head of Perseus is that it is temporary. Until her removal, Medusa will stand indignant, across the street from a criminal courthouse, reminding the public that through millennia women who are sexually assaulted are likely to be blamed.