Dr. Dara Kass gets at least a half-dozen calls every single day from friends and neighbors in Brooklyn and across the country. She is, for the people who have her phone number, like a “Covid concierge” — there to allay fears with facts and guide tough decision-making with science. And if you’ve seen her on MSNBC or follow her on Twitter, you may have also been soothed by the balm of her steady voice and sage advice.

An emergency room physician, a mom with young kids, and someone infected early on during the Covid pandemic — who has had to navigate the same challenges and questions and doubts as the rest of us, but armed with the medical and scientific insights most of the rest of us lack? Who the heck wouldn’t want her on speed dial?

Kass is a doctor in the Columbia University Medical Center E.R., and also an associate professor of emergency medicine. She’s been politically active for some time, as an advocate for increasing gender representation and equity in emergency medicine, and as an early and vocal supporter of Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign and now Andrew Yang’s campaign for New York City mayor. But it was Covid that made her phone, literally and metaphorically, start ringing off the hook.

“In the beginning of this pandemic, we all thought we’d watch it from far away,” Kass told me over the phone in late February 2021. But then it started getting closer… from China, to Italy, and then Seattle. She’s in all these online groups and email chains with emergency medicine doctors and by late February 2020, “all the channels were on fire.” People were getting infected, hospitals were filling up. “I was realizing this would hit us like a tidal wave.”

The next part of the story feels very Park Slope. Kass was walking back with her husband from their ritual Saturday morning Soul Cycle class on March 7, 2020. She was processing all of the information she was hearing about the disease and what they would do if she got infected. Suddenly, Kass stopped in her tracks and made a decision. They would move their kids to live with Kass’ parents in New Jersey on March 13, the day before Kass had her next shift at the E.R. A few days after that, Kass started experiencing Covid symptoms.

“I started making all these decisions for my family probably a hot minute before everyone else had to do it for theirs,” Kass says. “And being very public about the decisions I was making.” It was early, not much was known about Covid, how it was contracted and spread and the risk to various age groups. She did what was most prudent at the time — in a way setting up a clear contrast with her foil throughout this pandemic, the Trump Administration. While Kass and — thanks to her leadership and the leadership of others — many of the rest of us were taking the virus seriously and being as cautious as possible, Trump and his Administration were dismissing the threat and being reckless. Kass was making the smart decisions for herself and her family, and using her platform to share information about those decisions. Trump’s decisions was making dumb decisions — that ultimately destroyed us.

“Once we knew more and had an idea of how it was spreading,” says Kass, the Trump Administration could have put out “very specific, consistent guidelines of what people had to do.” But they didn’t. That was just one of many failures that compounded the crisis. “By the time New York was in the thick of it in April, we had an idea of how to stop it… but Trump was saying we’d be back by Easter, that the economy needs to open.” That’s when it became clear to Kass that the federal government was being what she calls “criminally negligent” in the face of this pandemic.

But did liberal states and cities, like New York, over-correct with extreme lockdowns? No, insists Kass. “What appeared to be an overreaction was supposed to be the only reaction. The goal was to have this be the time to react strongly and shut it down.” Yet because the national response was so spotty and inconsistent, the shut downs didn’t shut down the virus — ”and we didn’t have a lot of tools left in the toolbox.”

New York, fortunately, turned around. “We had a horrific March and April,” says Kass. But by the end of May, E.R. departments were mostly empty, she says. “We got a reprieve over the summer. And in the fall, patients didn’t come in as sick as before.” That’s not because the virus was better but because our preparedness was. There was better testing, people were coming into the E.R. earlier, there was more information on how to treat them, better medication options. And doctors and nurses felt more confident, too. “There’s a trauma about taking care of patients where you don’t understand what’s coming next.” Living through the first wave, including many health care workers surviving infections themselves, removed a lot of the sense of uncertainty.

That’s not to say it was easy. Kass recounts friends who spent weeks in the ICU, another who died by suicide. Her own symptoms were relatively mild. She feels fortunate. Though of course the lasting effects of working frontline during the pandemic may leave scars for generations.

At least, Kass says with a relieved sigh, things are getting better. For one, we have a competent president who believes in science and is mobilizing the full weight of the federal government to address this crisis. And second, we have vaccines.

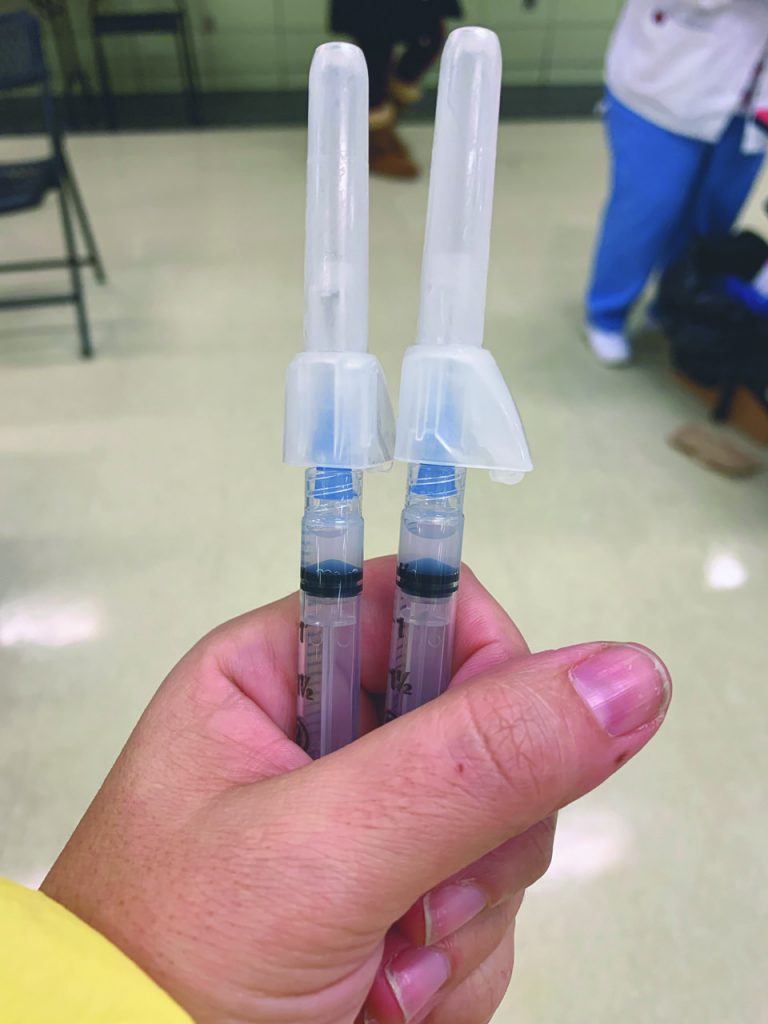

“The process of vaccinating people is healing,” says Kass, who has spent time working at vaccination sites. “Getting vaccinated is great, you feel protected… less nervous,” she says. But also, “Working at the sites, it’s life affirming… really rewarding.”

Kass thinks that soon New York will have enough supply to have walk-in vaccination spots all over the city. And she echoes President Biden, who recently predicted that every American who wants a vaccine will be able to get one by the end of May. What does that mean? The vaccine was tested to keep people from getting sick from the coronavirus and dying, and it does just that — very effectively. Beyond that, Kass uses the metaphor of a forest fire. We don’t yet know how well the vaccine prevents vaccinated people from spreading the virus to others; that wasn’t what it was tested to do. It likely does that well, says Kass — we’ll know more as more data become available. But in her forest fire metaphor, “If a tree can’t catch fire, it doesn’t matter as much if other trees are burning all around it.” And the more trees are fire proof, the more the blaze will be under control.

Beyond that, I used the opportunity with Kass to try to ask as many of the “Covid concierge” questions I thought might be on the minds of my fellow Park Slopers. So here, edited for length, is a rapid-fire Q&A with Dara Kass:

If I qualify to be vaccinated, should I nonetheless wait until higher risk people get their turns?

No. Everyone who is qualified to get vaccinated should get vaccinated as soon as it’s available. And that helps protect other people.

If my parents are vaccinated, can my kids hug them?

Yes. Your parents are protected from getting sick and dying. Which is remarkable.

If I’m vaccinated, can I go on vacation?

Yes. In fact, if you can find three other vaccinated people, you can all go on vacation together. You can start to incorporate reasonable risk back into your life.

If I’m vaccinated, do I have to quarantine after a possible exposure?

If it’s two weeks after your second vaccine shot, then no.

Can I get whatever vaccine is offered to me now and then another one later?

Maybe. This is an issue for people living in other countries where an inferior vaccine is available now, but they might want to get another when they’re back in the States. My advice is for now, take whatever vaccine is offered. It’s likely that, eventually, we’ll have enough supply or booster shots if there’s reason to believe you need or want it.

Can I send my kids to summer camp?

It’s very possible and likely — but will take parents engaging in reasonable quarantining, testing protocols and good strategies for well-controlled environments. It’s good for kids to run around outside and be healthy.

Should I feel okay sending my kids to in-person school?

Of course. In-person school is governed by things that have nothing to do with teacher vaccinations — but spacing requirements, quarantines, etc. But teachers should be a high priority for eligibility. I actually think we should have pop-up vaccination sites in schools, meet people where they are. We’d have everyone done in a month.

Once I’m vaccinated, do I still need to wear a mask?

Yes. Until we get it under control better, that’s the smarter, no-risk thing to do. And people are unevenly vaccinated right now. It’s important we all model mask wearing.

What kind of mask do you recommend most?

The most important thing is that it fits tightly. An unmasked gap undoes all the protections of whatever fancy mask you use. If you have a cloth mask, then you should have a disposable surgical mask under it — so the cloth mask generally helps create a tighter fitting seal.

What would you say to people who are worried the vaccines are too new and untested?

So is the virus. Let’s be honest, we’re in a pandemic. Every vaccine is new at some point. But it’s not untested; it’s been tested thoroughly. I do understand the anxiety about the speed, but I feel more anxiety about the speed of the pandemic.

Do you think fall will be normal?

Redefine normal. I think movie theaters will be open but a third of people will be wearing masks, even if they’re vaccinated. We have to figure out how schools will stay open, etc. But by Spring 2022, this won’t be the thing we’re talking about.