Eternal summer is a dream when you’re a kid. When you’re a parent, not so much. Every year, the final week of August drags on interminably, just like the final week of each of my pregnancies, and I find myself wondering, “What if Labor Day never comes? What then?” So, when dawn breaks on the first day of school every year, I am full of wonder and gratitude. I want to kiss the Department of Education full on the lips.

The only thing that tempers this relief is the stack of lunchboxes on the kitchen counter.

“Remember us?” the lunchboxes seem to hiss. “We’re baaaaaaack.”

Really, it’s one lunchbox in particular. The one belonging to my six-year-old daughter, known in these parts as Terza.

Terza is what’s commonly referred to as a picky eater, though “picky” is too demure and dainty a word to describe the iron-willed resistance she shows to consuming anything besides candy, crackers and pizza.

She has always been a discerning eater, even in the womb. She was so small in the sonograms, my obstetrician suggested I drink a milkshake daily to fatten her up. For the past six years, I’ve felt like a prince in a fairytale, only my quest is not to make the princess laugh, but to make the princess eat. Dinner and breakfast are hard enough but lunch, especially at school. is nearly impossible.

It’s a classic case of getting a taste of your own medicine. I, too, was a finicky eater.

My mother likes to recount how, when I was the age Terza is now, the only thing I’d bring to school for lunch was bread and water.

“Like a prisoner!” she exclaims.

I figured my mother could probably have stumbled upon an alternative to the prisoner meal, if only she’d tried a bit harder. This is the kind of asinine conclusion one makes before one has kids. When faced with Terza’s pickiness, I vowed to resolve the issue by trying hard, being creative and above all, listening to her input.

“What would you like for lunch at school tomorrow?” I asked her.

Once we worked through the unhelpful responses, “School? Don’t tell me I have to go to school again!” we arrived at the outlandish, “A hamburger and pasta with bechemel sauce.”

“How about mac and cheese?” I asked, searching for a feasible facsimile.

“Okay,” she replied. Convincingly, I should add. So I prepared mac and cheese in the morning and scooped it, fast, into her Thermos, so it would stay nice and hot for lunch.

In the evening, when I unscrewed the Thermos lid, I found it full. Chock full. Brimming over. The Thermos was so full, it looked like she’d added macaroni.

“You didn’t take a bite of your lunch!” I said.

“Mommy,” she replied. “I hate mac and cheese! Why did you put it in my lunchbox?”

I’m sure she didn’t mean to gaslight me. Still, I was tempted to record our conversations to play back for her later. Nonetheless, the important thing was figuring out what to pack for tomorrow.

“Nothing,” she said. “I hate lunch.”

“How about a cream-cheese sandwich?”

“Fine,” she agreed.

Of course, when I picked up Terza from school the next day, her lunchbox was full and her stomach was empty. She was ravenous.

“Please, Mommy, can I have a bagel?” she begged, rivaling Oliver Twist in pathos. “I’m . . . just . . . so . . . hungry. I feel faint!”

I procured her a bagel. I am an Italian mother after all. I am wired to feed children.

Watching her devour the bagel, I proposed that maybe she might enjoy a bagel in her lunchbox tomorrow,

Naturally, she agreed.

You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to deduce what happened next.

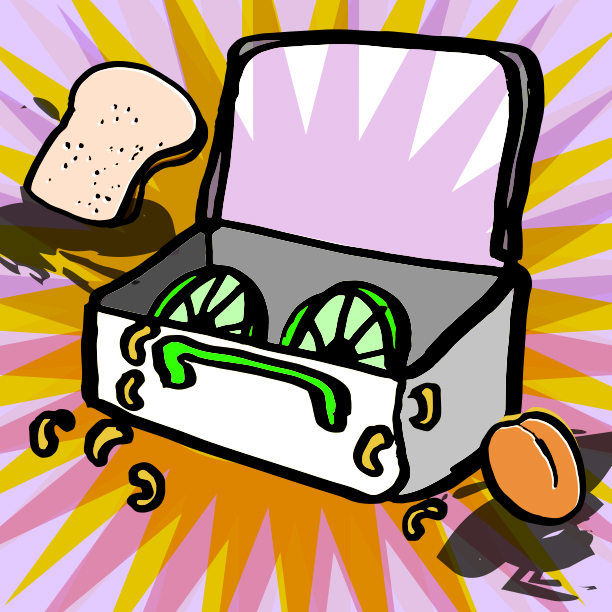

No matter what went in the lunchbox, it was returned uneaten. I began to suspect that Terza had a Magic Lunchbox. A Dark Magic Lunchbox. It made delicious things repellant. Except, strangely, for cookies. Those are immune.

The solution was clear. School lunch. She didn’t eat that either–found it even more distasteful than anything I could prepare–but at least I didn’t have to toil over a steaming stove at 7 in the morning only to find the fruits of my labor untouched. School lunch seemed like a perfect solution to my problem, if not to hers. But the problem with parenting is your kids’ problems, really, are your problems too. Eventually, her pleading wore me down.

“Please, Mommy, can’t you make me lunch?” she’d beg. “Don’t you want me to eat?”

Finally, I did the only thing I knew worked with picky eaters. Bread and water.

In my defense, I added a peach.

Because the peach was never eaten, I just left it in the lunchbox, day after day, whether from optimism or laziness, I’m not sure. Day after day, I persisted in my war of attrition with the peach. Day after day, I watched it grow more bruised and mangled. Finally, I could take it no longer. I euthanized the poor fruit. And I quit packing lunch.

I am a determined person who tackles problems pro-actively, believing that with enough stamina and flexibility, one can find a solution to any conundrum, no matter how thorny. I am a person who is sometimes wrong.

As a parent, of course, you have to keep trying. Or at least, someone does. Which is why I decided to pass the baton to my husband.

“Here,” I said, handing over the Dark Magic Lunchbox. “Good luck.”

“What should I pack?” he asked, innocent that he was.

I smiled. “Why don’t you ask her?”

Nicole C. Kear is the author of The Fix-It Friends, a chapter book series for children (Macmillan Kids), as well as the memoir Now I See You (St. Martin’s Press).

Art by Heather Heckel